A shortage of respiratory ventilators in the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to numerous well-meaning ventures that include assembly lines converted from autos to ventilators and a DIY ventilator open-source home-project craze. But neither of these approaches are likely to do much for getting ventilators fielded fast enough to help with flu patients. GM and Ford, for example, expect to produce 80,000 ventilators by late summer, a number exceeding the estimated total now in U.S. hospitals. But experts say a late-summer delivery date won’t help with the COVID-19 patient surge expected to hit in mid to late spring.

A better approach, say a group of veteran ventilator builders, is to refurbish old decommissioned ventilators tucked away in dark corners of hospital storage rooms.

That’s the idea behind a not-for-profit corporation called Co-Vents, formed to obtain and repair ventilators during the pandemic. The founders have six FDA-approved and ISO-certified ventilator service centers lined up in New Jersey, Tenn., Calif., Ill. and Georgia. Co-Vents says it is looking for decommissioned Puritan Bennett, Philips/Respironics and CareFusion critical care ventilators to refurbish. If it gets a ventilator that is beyond repair, it will use the machine for parts.

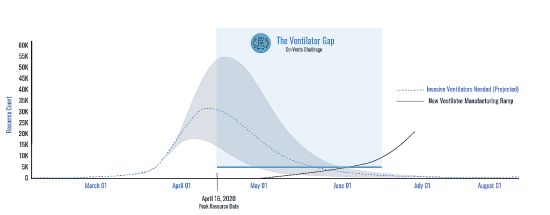

A graph from Co-Vents illustrates the delay involved with new ventilator manufacturing capacity compared with what can be accomplished by refurbishing decommissioned vents.

Once it’s rolling, Co-Vents is shooting for a turnaround time of just over a week and hopes to deliver 500 to 1,500 repaired or refurbished ventilators in the next two months. Co-founder Michael Raymer says Co-Vents acquired its first tranche of ventilators the week of April 6. Raymer says Co-Vents is forecasting a cycle time of one week from acquisition/donation to live clinical use.

Co-Vent cofounder Mike Raemer points out that starting with existing ventilators having designs that have already been approved by the FDA is a lot more likely to ease a shortage than setting up new ventilator assembly lines in converted auto factories.

A point also favoring refurbishment rather than making new machines is that the testing protocols for refurbished ventilators are relatively straightforward. A Co-Vent official explains it this way: “After the refurbished machine has passed its initial tests, you run it at temperature for a few days and test it again. If it passes, it is good to go. The FDA approves the process but they don’t monitor every machine.”

The service centers that Co-Vent is setting up are FDA and ISO-certified. Certification heads off problems that can arise when health care facilities try to refurbish older ventilators themselves. Ditto for difficulties encountered by well-intentioned but inexperienced technicians working from ventilator repair manuals downloaded from the Internet. In this regard, lack of tribal knowledge about specific machine idiosyncrasies can slow the repair process.

An anecdote from one engineering health care consultant illustrates the problem. “I was consulting at a certain hospital that had a defective heart and body monitor in for repair,” he says. “The problem was quickly determined to be a failed primary input circuit board. They had a known-good spare unit, and they swapped it in just to confirm the diagnosis. It didn’t work either. Fortunately there was yet another known-good unit on the shelf, so they tried the board from that one. It too failed. Then they put the good boards back in the known-good units and found that they now failed too. It turns out the maintenance manual forgot to mention something trivial but consequential: Don’t handle the circuit boards! Finger oils across a few traces and contacts screwed up the astronomically high resistances on the board. They all had to be sent back to be cleaned and recertified.”

You may also like:

Filed Under: Fighting COVID-19