If you’re a design engineer working for an industry behemoth that buys components by the million, it’s relatively simple to get some samples or a little help understanding a new datasheet. You pick up the phone, call the manufacturer directly, and then their local sales or applications engineer will scramble to get whatever you need.

Figure 1: Large distributors use training as a key way to become involved earlier in the design process. Shown are attendees at Avnet’s X-Fest 2014. (Source: BusinessWire)

Major suppliers tend to concentrate most of their in-house resources on the care and feeding of a relatively small number of “direct accounts” who get red-carpet treatment. Understandable, but too bad if you’re a second- and third-tier OEM. Apart from answering questions via their online forum, manufacturers won’t give you the time of day, and you’ll be referred to one of their network of distributors.

Increasingly, though, that gives you access to a range of products and services that exceeds those offered by a single manufacturer to even their largest direct customer.

The Changing Nature of the Market

Distributors have long offered services to help customers manage their supply chains. Same-day shipping, in-plant or remote stores, kitting, and automatic inventory replenishment help customers implement just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing concepts, and distributors are adding other supply-chain related tools.

Future Electronics, for example, offers a quarterly market conditions report. For each segment—logic, analog, capacitors, etc. —and manufacturer, there’s an indication of pricing trends compared to the previous quarter, current lead times, lead time trends, and pertinent comments from the Future marketing group.

Back when I started in the late 70s, distributors didn’t offer much in the way of in-house design and applications engineering expertise. But as Bob Dylan said, “The times they are a changin.” Distributors are now offering a host of design services in an attempt to become a partner at all stages of the design process, from initial concept to volume production.

Of course, there’s a healthy dose of self-interest at work here: the earlier a distributor can become involved in the design process, the better the opportunity to influence component selection.

Two trends that are encouraging distributors to augment their expertise are the rise of open-source hardware and the Internet of Things (IoT)—yes, that again.

Open-Source Hardware and the Maker Movement

Open-source software has been a thorn in the side of Microsoft, Oracle, and their ilk for years, but manufacturers such as Arduino, Sparkfun, Adafruit, and others are releasing schematics, PCB layouts, parts lists, etc. under a variety of open licenses that give experimenters wide latitude to tinker and make modifications.

Sharing HDL code to help others duplicate designs on standard FPGAs is another manifestation of open-source hardware; aficionados have their own website where you can download code for 10/100 Ethernet MACs, RISC architectures with DSP features, AES modules, and even an open-source version of TI’s MSP430 low-power microcontroller, albeit with a different feature set.

These developments have opened up the field to a host of “enthusiastic amateurs,” and many distributors are actively supporting the open-source hardware movement. Check out Mouser’s Open-Source Hardware page, which includes a variety of projects released under the Creative Commons license.

It’s very difficult to predict which hobby shop operation may spawn the technology of tomorrow, so other distributors are increasingly providing online resources aimed at developers of all ages and experience levels—what RS Components’ Glenn Jarrett has called the “Business to Geek” (B2G) market. In support of B2G, RS has DesignSpark, which offers free design tools such as 3D mechanical design software, PCB layout software, and an online database of engineering models.

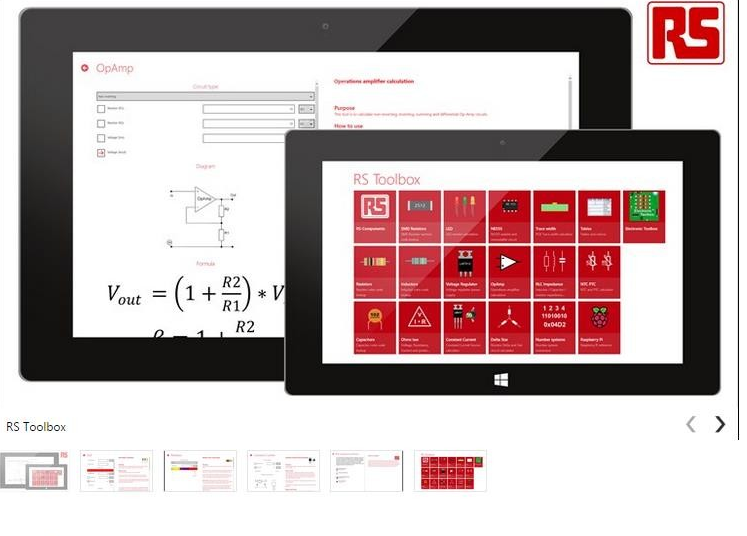

Figure 2: Part of the DesignSpark suite of online tools, the RS Toolbox offers an array of calculation tools and reference material in one desktop or mobile app. (Source: RS Components)

Closely related to the Rise of the Geek is the Maker Movement. A “maker” can be loosely defined as someone who derives meaning from the act of creation. It includes generations of artisans, backyard car customizers, tinkerers, and inventors of all stripes. Many makers don’t have formal training, and there are few opportunities for million-dollar design wins, but thousands of small-volume customers are there for the taking: in 2015, there were 151 Maker Faires worldwide to showcase maker projects, which attracted over one million attendees.

Just the thing to get a distribution sales executive’s attention, one would think. Arrow, Digi-Key, and Mouser apparently agree: they’re all Maker Faire sponsors.

The Internet of Things

In addition to providing writing opportunities for freelancers like me, the IoT has led to a rash of startups trying to get a piece of the action. But developing an IoT product is hardly a non-trivial task; it requires expertise in a variety of technologies such as wireless connectivity, power management, sensors, connectors, and packaging, among others. Developing an IoT product can be challenging for small companies that don’t usually have the breadth of in-house technical knowledge needed.

Enter the distributor: not only do they have development kits that are optimized for IoT quick-start development, but in many cases, they provide training too. As I mentioned last month, Arrow and Renesas have teamed up to offer seminars on Renesas’ IoT Enabler Kit at local Arrow offices around the U.S.

Later, once the new product goes into production, the company may need help with forecasting demand and managing inventory. Startups have limited capital, and they want to use it to develop new products and for marketing—not to build warehouses to hold inventory.

Casting The Net Wide: Other Services

If you run a larger operation, such as Avnet with FY2016 sales of $26.2 billion, or Arrow, with 2015 sales of $23.3 billion, you can perhaps afford to expand your horizons. Both companies are busily diversifying into related service areas.

Avnet has perhaps the most diversification: their Technology Solutions services group accounted for around 37 percent of 2016 revenue. The company has gone into hosting services and cloud-based products in a big way: according to the website, its StadiumEdge product “lets you connect the dots from disparate data sources through a single view and gain deep insight” that can boost ticket sales, optimize resource allocation, and increase concession sales, among other things.

Hey, design engineers are sports fans too.

Avnet has also staked a claim to the B2G market with its acquisition of British distributor Premier Farnell, a leading maker of the Raspberry Pi low-cost computer board.

Sticking closer to home, Arrow’s Power Supply group in Phoenix, Arizona offers design services including: build-to-print; testing, inspection, and burn-in; sheet metal, PCB, and cable assembly design services; kitting; product testing and documentation; system design and integration; and others.

There’s more than one way to skin a cat. Distributors are also trying to influence designer decision-making in more subtle ways. For example, in June, Arrow purchased a group of electronic trade publications from UBM that includes EE Times, EDN, and Electronic Products. The company’s new corporate home will be Arrow’s Aspencore group.

Distributors aren’t neglecting future designers either, as evidenced by the Avnet Innovation Lab at Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. The lab is part of a $750,000 donation over three years that will award funding to selected entrepreneurs and provide connections to help bring their technologies to market.

Where were they when I needed funding for my Perpetual Motion/Cold Fusion/Fountain of Youth machine?

Filed Under: Industrial automation