Researchers have developed a stretchable, flexible patch that could make it easier to perform ultrasound imaging on odd-shaped structures, such as engine parts, turbines, reactor pipe elbows and railroad tracks—objects that are difficult to examine using conventional ultrasound equipment.

The ultrasound patch is a versatile and more convenient tool to inspect machine and building parts for defects and damage deep below the surface. A team of researchers led by engineers at the University of California San Diego published the study in the Mar. 23 issue of Science Advances.

The new device overcomes a limitation of today’s ultrasound devices, which are difficult to use on objects that don’t have perfectly flat surfaces. Conventional ultrasound probes have flat and rigid bases, which can’t maintain good contact when scanning across curved, wavy, angled and other irregular surfaces. That’s a considerable limitation, said Sheng Xu, a professor of nanoengineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and the study’s corresponding author. “Nonplanar surfaces are prevalent in everyday life,” he said.

“Elbows, corners and other structural details happen to be the most critical areas in terms of failure—they are high stress areas,” said Francesco Lanza di Scalea, a professor of structural engineering at UC San Diego and co-author of the study. “Conventional rigid, flat probes aren’t ideal for imaging internal imperfections inside these areas.”

Gel, oil or water is typically used to create better contact between the probe and the surface of the object it’s examining. But too much of these substances can filter some of the signals. Conventional ultrasound probes are also bulky, making them impractical for inspecting hard-to-access parts.

“If a car engine has a crack in a hard-to-reach location, an inspector will need to take apart the entire engine and immerse the parts in water to get a full 3D image,” Xu said.

Now, a UC San Diego-led team has developed a soft ultrasound probe that can work on odd-shaped surfaces without water, gel or oil.

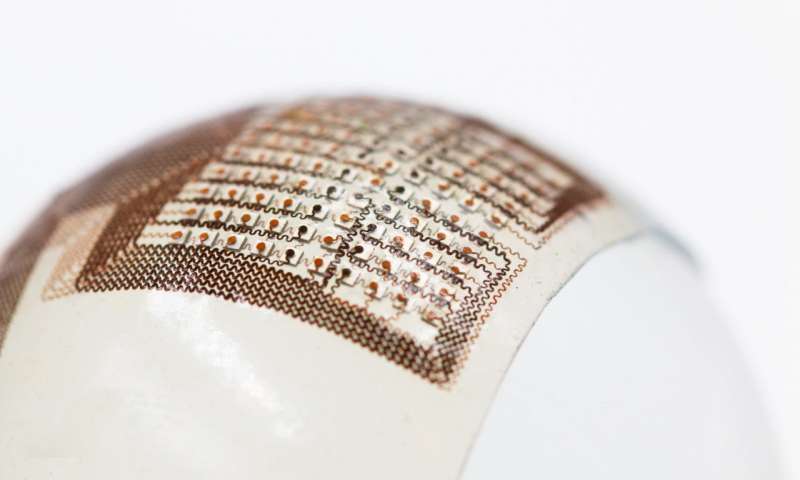

The probe is a thin patch of silicone elastomer patterned with what’s called an “island-bridge” structure. This is essentially an array of small electronic parts (islands) that are each connected by spring-like structures (bridges). The islands contain electrodes and devices called piezoelectric transducers, which produce ultrasound waves when electricity passes through them. The bridges are spring-shaped copper wires that can stretch and bend, allowing the patch to conform to nonplanar surfaces without compromising its electronic functions.

Credit: Hongjie Hu, University of California at San Diego

Filed Under: Materials • advanced