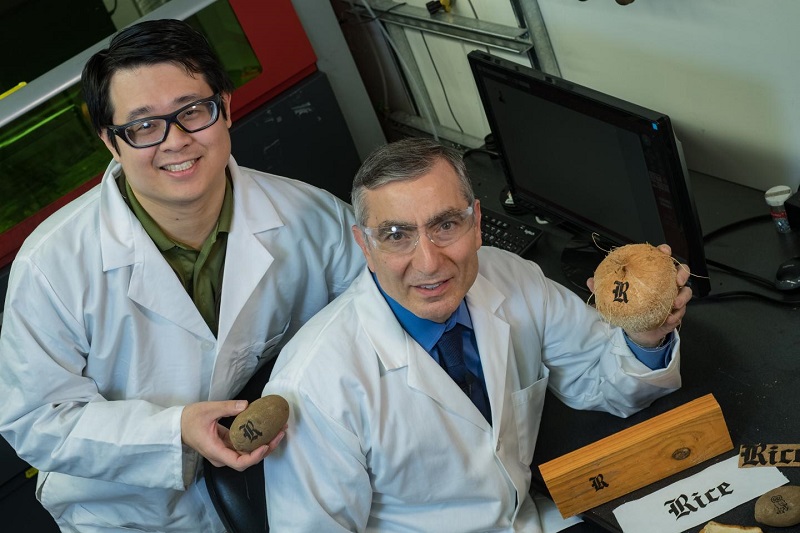

This is Rice University graduate student Yieu Chyan, left, and Professor James Tour. Image credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Rice University scientists who introduced laser-induced graphene (LIG) have enhanced their technique to produce what may become a new class of edible electronics.

The Rice lab of chemist James Tour, which once turned Girl Scout cookies into graphene, is investigating ways to write graphene patterns onto food and other materials to quickly embed conductive identification tags and sensors into the products themselves.

“This is not ink,” Tour said. “This is taking the material itself and converting it into graphene.”

The process is an extension of the Tour lab’s contention that anything with the proper carbon content can be turned into graphene. In recent years, the lab has developed and expanded upon its method to make graphene foam by using a commercial laser to transform the top layer of an inexpensive polymer film.

The foam consists of microscopic, cross-linked flakes of graphene, the two-dimensional form of carbon. LIG can be written into target materials in patterns and used as a supercapacitor, an electrocatalyst for fuel cells, radio-frequency identification (RFID) antennas and biological sensors, among other potential applications.

The new work reported in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano demonstrated that laser-induced graphene can be burned into paper, cardboard, cloth, coal and certain foods, even toast.

“Very often, we don’t see the advantage of something until we make it available,” Tour said. “Perhaps all food will have a tiny RFID tag that gives you information about where it’s been, how long it’s been stored, its country and city of origin and the path it took to get to your table.”

He said LIG tags could also be sensors that detect E. coli or other microorganisms on food. “They could light up and give you a signal that you don’t want to eat this,” Tour said. “All that could be placed not on a separate tag on the food, but on the food itself.”

Multiple laser passes with a defocused beam allowed the researchers to write LIG patterns into cloth, paper, potatoes, coconut shells and cork, as well as toast. (The bread is toasted first to “carbonize” the surface.) The process happens in air at ambient temperatures.

“In some cases, multiple lasing creates a two-step reaction,” Tour said. “First, the laser photothermally converts the target surface into amorphous carbon. Then on subsequent passes of the laser, the selective absorption of infrared light turns the amorphous carbon into LIG. We discovered that the wavelength clearly matters.”

The researchers turned to multiple lasing and defocusing when they discovered that simply turning up the laser’s power didn’t make better graphene on a coconut or other organic materials. But adjusting the process allowed them to make a micro supercapacitor in the shape of a Rice “R” on their twice-lased coconut skin.

Defocusing the laser sped the process for many materials as the wider beam allowed each spot on a target to be lased many times in a single raster scan. That also allowed for fine control over the product, Tour said. Defocusing allowed them to turn previously unsuitable polyetherimide into LIG.

“We also found we could take bread or paper or cloth and add fire retardant to them to promote the formation of amorphous carbon,” said Rice graduate student Yieu Chyan, co-lead author of the paper. “Now we’re able to take all these materials and convert them directly in air without requiring a controlled atmosphere box or more complicated methods.”

The common element of all the targeted materials appears to be lignin, Tour said. An earlier study relied on lignin, a complex organic polymer that forms rigid cell walls, as a carbon precursor to burn LIG in oven-dried wood. Cork, coconut shells and potato skins have even higher lignin content, which made it easier to convert them to graphene.

Tour said flexible, wearable electronics may be an early market for the technique. “This has applications to put conductive traces on clothing, whether you want to heat the clothing or add a sensor or conductive pattern,” he said.

Filed Under: Materials • advanced