They call it “the Lab-in-a-Box.” According to Nadir Weibel, a research scientist in the Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) department at the University of California, San Diego, inside the box are assorted sensors and software designed to monitor a doctor’s office, particularly during consultations with patients. The goal is to analyze the physician’s behavior and better understand the dynamics of the interactions of the doctor with the electronic medical records and the patients in front of them. The eventual goal is to provide useful input on how to run the medical practice more efficiently.

They call it “the Lab-in-a-Box.” According to Nadir Weibel, a research scientist in the Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) department at the University of California, San Diego, inside the box are assorted sensors and software designed to monitor a doctor’s office, particularly during consultations with patients. The goal is to analyze the physician’s behavior and better understand the dynamics of the interactions of the doctor with the electronic medical records and the patients in front of them. The eventual goal is to provide useful input on how to run the medical practice more efficiently.

Very often physicians pay attention to information on a computer screen, rather than looking directly at the patient. “With the heavy demand that current medical records put on the physician, doctors look at the screen instead of looking at their patients,” says Weibel. “Important clues such as facial expression, and direct eye-contact between patient and physician are therefore lost.”

The first findings from the project are just-published in the February 2015 edition of the journal, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing* and have been highlighted by the New Scientist magazine. The Lab-in-a-Box solution could capture multimodal activity in many real-world settings, but the researchers focused initially on medical offices and the problem of the increasing burden on physician introduced by digital patient records.

The Lab-in-a-Box has been developed as part of Quantifying Electronic Medical Record Usability to Improve Clinical Workflow (QUICK), a running study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and directed by Zia Agha, MD. The system is currently being deployed at the UC San Diego Medical Center, and the San Diego Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center.

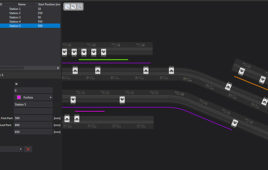

The compact suitcase contains a set of tools to record activity in the office. A depth camera from a Microsoft Kinect device records body and head movements. An eye tracker follows where the doctor is looking. A special 360-degree microphone records audio in the room. The Lab-in-a-Box is also linked to the doctor’s computer, so it can keep track of keyboard strokes, movements of the mouse, and pop-up menus that may divert the doctor’s attention.

The greatest value of the Lab-in-a-Box, however, is in the software designed to merge, synchronize and segment data streams from the various sensors – assessing the extent to which a certain confluence of activity may lead to distraction on the part of the physician. For example, says Weibel, lots of head and eye movement would suggest that the doctor is multitasking between the computer and the patient.

Weibel and the UC San Diego/VA team will compare data from different settings and different types of medical practice to pinpoint those factors that lead to distraction across the board, or that affect only specific medical specialties. Their findings could help software developers write less-disruptive medical software. The researchers envision also deploying the Lab-in-a-Box permanently in a doctor’s office to provide real-time prompts to warn the physician that he or she is not paying enough attention to a patient.

“In order to intervene effectively, we need to first understand the complex system composed by patients, doctors, and electronic medical record in depth, and this is what our study will finally yield.” says Weibel. Ultimately, as Weibel and his co-authors state in their original Personal and Ubiquitous Computing article, the Lab-in-a-Box “has the potential to uncover important insights and inform the next generation of Health IT systems.”

For more information visit http://www.ucsd.edu.

Filed Under: M2M (machine to machine)