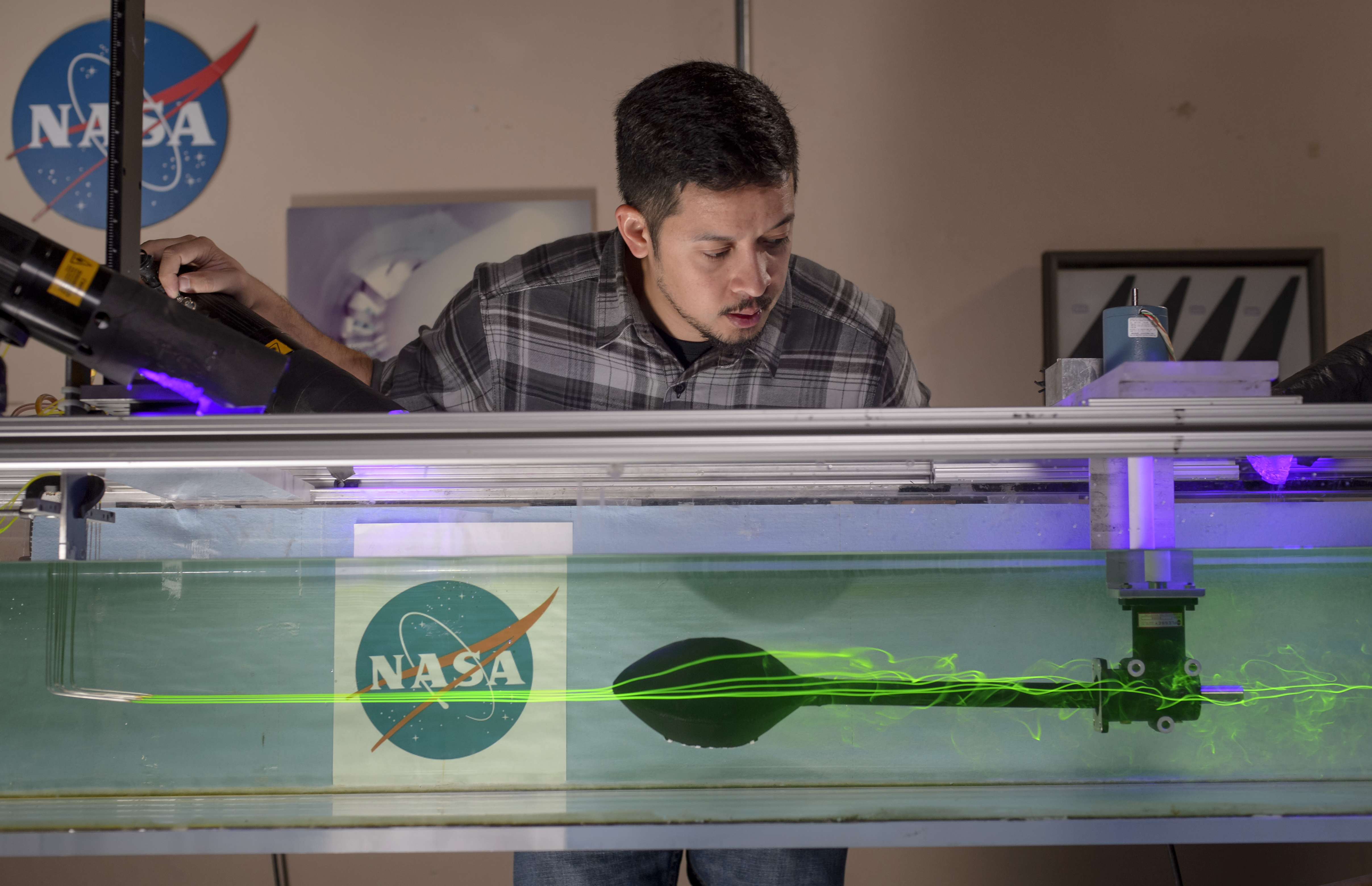

Student intern Joe Burces at NASA’s Ames Research Center observes football in fluid dynamics chamber. (Credits: NASA Ames / Dominic Hart)

Aerodynamics is the study of how air and liquids, referred to collectively as “fluids,” flow around objects. By understanding how fluids flow around basic shapes such as cylinders and spheres, NASA’s engineers predict how even minor alterations in these basic shapes change flow patterns and possibly make aircraft more Earth-friendly or help a spacecraft take the most efficient route to Mars.

With NASA’s Ames Research Center located less than ten miles from the home of Super Bowl 50 – Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, – its aerodynamics researchers have taken the opportunity to connect their science to something more unexpected: sports balls.

“Sports provide a great opportunity to introduce the next generation of researchers to our field of aerodynamics by showing them something they can relate to,” said Rabi Mehta, chief of the Experimental Aero-Physics Branch at Ames.

The way air moves around different shapes plays a significant role in the flight of all sports balls. What is the best way to throw a football? Why does a curve ball curve, why does it knuckle? Researchers can demonstrate the science behind these complex questions using relatively simple visualizations of fluids flowing over sports balls in small test facilities at Ames.

Complementing the large and high-speed wind tunnels at Ames, small wind tunnels and water channels used for quick tests provide controlled environments where fluids at known speeds can flow over a stationary test item – in this case a sports ball. With smoke, lasers or brightly colored dyes inserted in the fluid flow, patterns of smoothness and disturbance appear, making the usually invisible aerodynamics around the items brilliantly visible.

“What we are looking for in the smoke patterns is at what speed the smoke patterns suddenly change,” said Mehta. “There is a thin layer of air that forms near the ball’s surface called the ‘boundary layer,’ and it is the state and behavior of that layer that is critical to the performance of the ball. The materials used, the ball’s surface roughness and its distribution determines its aerodynamics.”

For example, a smooth golf ball travels less than half the distance of a dimpled one. The dimples make the boundary layer “turbulent” which keeps the boundary layer attached to the object longer and delays separation. When the boundary layer separates from an object, drag is created from the resulting pressure imbalance, and the object slows down.

“A football is shaped like a wing and more aerodynamic than a round ball so the flow is very different,” said Mehta. “When a quarterback throws the football he ideally wants to throw a tight spiral with high rotation rate to help stabilize the ball as it flies through the air. This produces lower drag than a wobbling ball so it will get there faster. Wobbling balls are also harder for the receiver to catch and more easily picked off by the defense.”

Kicking is another aspect of football aerodynamics, “We’ve all seen how critical the final kick can be, if the ball is a little bit off you can lose the whole game and the entire season,” said Mehta. Ideally the kicker should kick the ball so that it spins along the horizontal axis, if angled the ball veers sideways.

If football players can learn more about velocity, direction of motion and spin rates, they can learn how to achieve desirable results, he said. Mehta has spoken directly with athletes, using visual tools to illustrate aerodynamics concepts.

“I’ve witnessed it quite often,” Mehta said. “The understanding on their faces is remarkable, and that, I find very gratifying.”

He said many people can throw and spin the ball well, “but not with five 300-pound linemen coming at you.” That’s where even just a basic understanding of aerodynamics might make the difference between which team brings home Super Bowl 50’s Vince Lombardi Trophy and which will leave Silicon Valley empty-handed.

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense