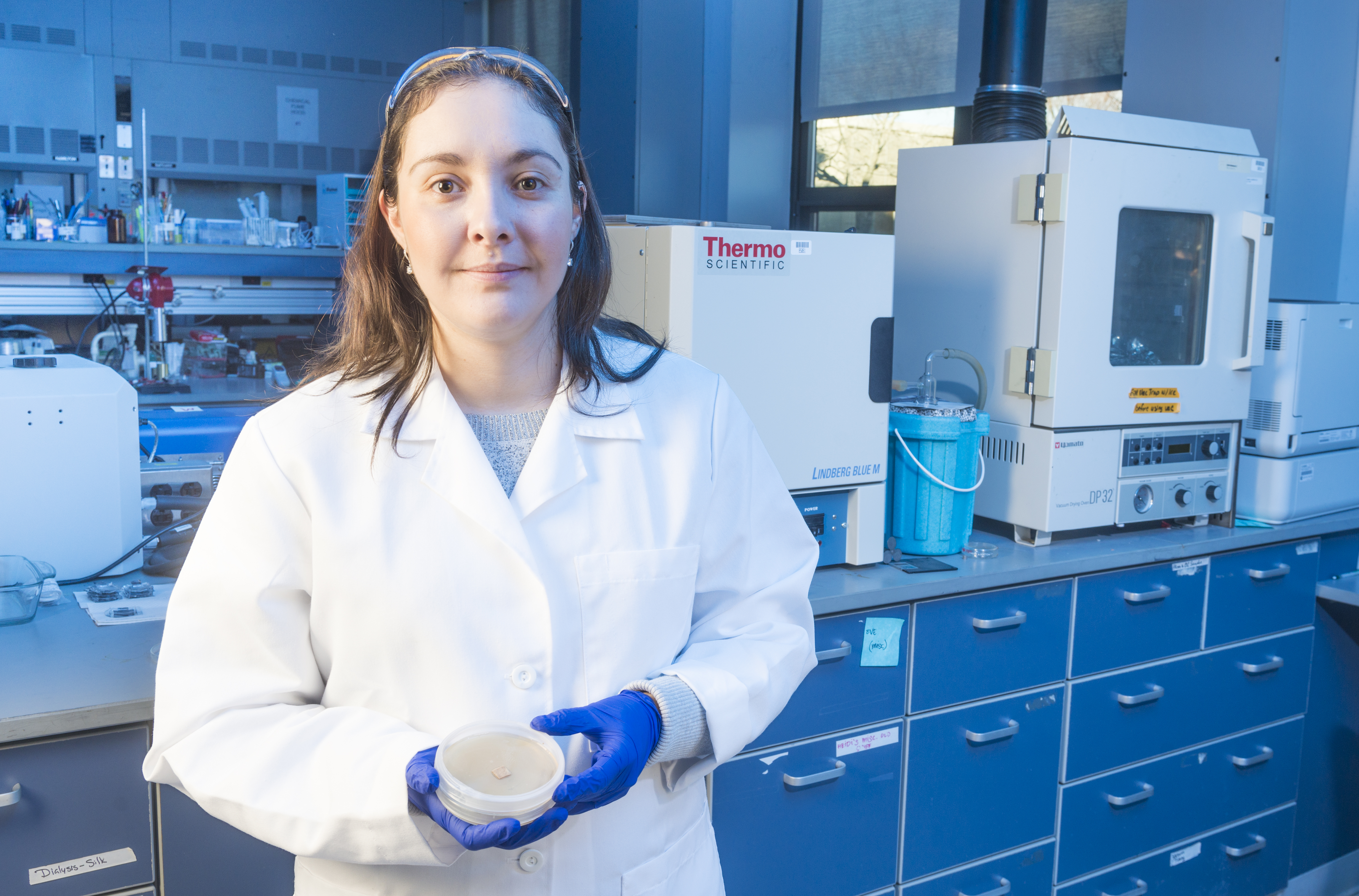

Dr. Paola D’Angelo, a research bioengineer at the U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, is working on second-skin, chemical-biological protection. The technology will be incorporated into one thin layer of protective fabric and will block and deactivate a number of threats. NSRDEC is working in collaboration with other defense labs and academia. (Photo Credit: David Kamm, NSRDEC)

Collaboration has long been second nature for researchers at the U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, and now a partnership is developing “second-skin,” chemical-biological protection.

NSRDEC is working with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of California at Santa Barbara, the Air Force Civil Engineering Center, and the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center to develop second skin, the next generation of chemical-biological protection for the warfighter. The Defense Threat Reduction Agency sponsors the project, which is a high-priority effort.

“The second skin will be a protective ‘skin’ engineered with textile materials as a substrate that will adapt to the environment that the Soldier is in,” said Dr. Paola D’Angelo, an NSRDEC research bioengineer. “The idea is that the skin will be lightweight, it will not retain heat, and it will be air and moisture permeable.”

“The material design is based on the use of responsive polymer gels, including organohydrogels and functional chemical species such as catalysts,” said Dr. Ramanathan “Nagu” Nagarajan, senior research scientist for Soldier Nanomaterials at NSRDEC. “The second skin will be able to sense chemical and biological agents, which will trigger a response within the gels.

“The response will close the pores of the textile, keeping the chemical or biological agent from entering. During this protection state, the threats will also be inactivated, allowing the second skin to return to its normal state.”

“Anthrax, for instance, is one of the biggest threats,” D’Angelo said. “So we need to find a way to detect it and kill it onsite. So the second skin not only senses the chemical or biological agent but it also has a response. It has a protection component as well as a deactivation component to it.”

The technology will enhance Soldier safety by addressing multiple threats, and it will allow a Soldier to continue doing his or her job without interruption. The technology will be incorporated into one thin layer, which will reduce a Soldier’s logistical burden. It is designed to act autonomously without any Soldier intervention.

“The Air Force Civil Engineering Center collaborators are developing the catalyst particles to counter mustard agents at the surface of the second skin,’ said Nagarajan. “The MIT collaborators are developing novel polymers to sense and inactivate anthrax spores at the second-skin surface.

“The MIT and UCSB collaborators are developing hydrogels and organohydrogels that will go into the second-skin interior to protect against nerve agents and blister agents while also sensing and inactivating them. NSRDEC researchers are integrating the components to create the second skin material and, along with ECBC collaborators, are testing the performance of the second skin against chemical and biological threat agents.”

“It’s a great effort,” said D’Angelo. “It gives us the opportunity to work with collaborators from other government labs and with universities. We can leverage one another’s expertise. All of us working together is much more effective than working alone.”

“I collaborate with Paola on various aspects of the DTRA project, designing and synthesizing reactive polymers capable of killing bacteria and spores,” Dr. Lev Bromberg said, a research scientist in the Department of Chemical Engineering at MIT. “I prepare the samples, characterize properties and discuss Paola’s experimental results.”

Dr. David McGarvey, a research chemist at ECBC, and ECBC’s Dr. William Creasy provided expertise in the testing of the technologies against hazardous chemicals.

“The greatest benefit of the collaboration is that it has allowed each of us to do what we do best,” McGarvey said. “Entering into a completely new area of research can be fun, but it takes time and resources to develop a new expertise. With very limited funding, our group of collaborators was able to quickly create and test a number of new technologies.”

The collaboration also gives university students and postdoctoral researchers the opportunity to work with top Army scientists, including NSRDEC’s Dr. Eugene Wilusz and Nagarajan.

“Working with Wilusz and Nagu is an excellent experience and opportunity,” said Manos Gkikas, a postdoctoral researcher at MIT. “They are both very supportive and communicative.”

Communication is key to the collaboration.

“We meet frequently to generate ideas, share expertise, and to make sure what we are doing is compatible,” said D’Angelo.

“Program reviews led by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency Chem-Bio division were very helpful in allowing collaborators from many different parts of the nation to engage in face-to-face dialog about the program,” McGarvey said. “These discussions helped everyone understand the overall progress of the research and develop a deep understanding of the challenges each group was undertaking. With everyone in the same room, a number of very helpful brainstorming sessions took place that resulted in new approaches for the research problems each group faced.”

“Our group at MIT has been working with Natick for a number of years. We have established a good rapport and have been working on a number of projects” said Bromberg. “We surely hope to continue working with Natick.”

“Everyone is coming together for the Soldier,” said D’Angelo. “It is a good feeling. I really like the interactions we have with Soldiers here and seeing what we are doing applied to the Soldiers. Sometimes if you are doing research for a company you don’t see it going anywhere. Here we see it in person. We see it being applied to protect Soldiers.”

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense