A few years ago, architect Sean Burke, LEED AP, was working as a consultant in Seattle’s industrial SoDo District when he had an epiphany.

He’d spent part of his days staring out the window at stacks of shipping containers and also thinking about small living spaces. At some point, the lightbulb clicked on, and he began planning and designing a shipping-container home to call his own. Shipping-container dwellings are not new, of course, but Burke decided to push the envelope with his design.

“All the [shipping-container houses] I’d seen were just many stacked together—in the way they are meant to be stacked,” Burke says. “I wanted to look at a single box that’s a little bit different, by chopping it up strategically, making it feel more open by letting in light and lifting up part of the roof.”

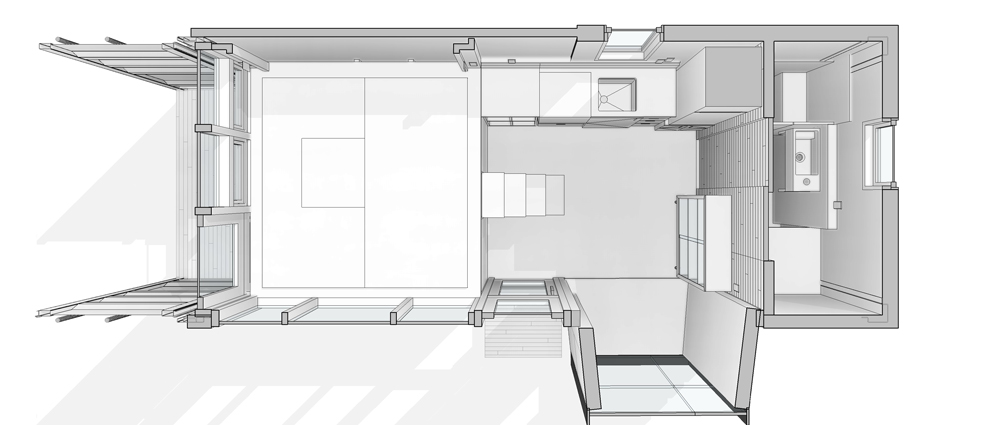

Bento Box project drawing. Courtesy Sean Burke and Unboxed House.

No longer simply industrial boxes or even showy boutique dwellings, shipping-container architecture has come of age. Ever since the first patent for a container house was issued in the late 1980s, the concept of converting these heavy steel units into housing has been growing in popularity.

Proponents point to their inherent strength, wide availability, and the relatively low costs associated with transporting and building with the containers. Sustainability advocates also tout the container’s high levels of embodied energy, low carbon footprint, and durability in the face of storms and other natural events—what green-building advocates have been calling “resiliency.”

“These containers are built to last, which is more environmentally conscious,” Burke says. “You can move them. They are useful if you want to be less tied to a single physical location and yet still want the feeling of home and stability.”

Bento Box project drawing. Courtesy Sean Burke and Unboxed House.

In terms of design, however, shipping-container residences have often looked just like themselves—stacks of rectangles with a few window and door openings thrown in. The uniform size of the average shipping container (usually 40 feet long by 8 feet wide by 9.5 feet high, for 320 square feet and 3,040 cubic feet of living/storage space) is both a blessing and a curse.

It’s easy to figure out the footprint when multiplying containers, but it’s also easy to be confined by their rectangularity. “You’ll see these little backyard home offices and cottages made out of containers,” Burke says, “but very few people are selling them as a single-unit full-time living quarters.”

SeaUA apartment building in Washington, DC. Courtesy Travis Price Architects.

In terms of style and ambition, however, shipping-container homes have undergone a renaissance in recent years, with architects pushing the limits of design. Calling his blog and brand the Unboxed House, Burke sought to demonstrate that shipping containers could be viable as long-term primary living spaces and that they could behave more like large-scale LEGOs than simple stacking blocks.

Using Autodesk FormIt 360 and Revit to work out the design for his Bento Box project, Burke popped out the end and side of his house (now under construction) and pushed up the top to add a shed roof, with a long bank of windows on one side. His budget? Only about $25,000.

This kind of innovation is happening in other parts of the world, too, especially in areas where affordable housing is in demand. Five years ago, architect Benjamin Garcia Saxe created a shipping-container home in Costa Rica, for a family that wanted to live debt-free, using two reclaimed 40-foot shipping containers. But he offset them laterally and inserted a gap corridor in between, adding a slanted roof over the new section. This unusual shape, along with clerestory and floor-to-ceiling windows, made the space feel bigger. The project was a mere $40,000.

“The idea of using shipping containers came from my clients,” Garcia Saxe says. “They found a couple of very cheap, almost destroyed, banged-up, and rusted shipping containers for a very low price and bought them. I then had to help them work miracles. Reusing a material that has been discarded is really great and cost-effective. The metals used in containers are very durable and hard to buy off the shelf.”

SeaUA kitchen and living room. Courtesy Travis Price Architects.

Meanwhile, the SeaUA apartment building near Catholic University in Washington, DC, which was completed in 2014, has three levels with six shipping containers each. Designed by Travis Price Architects (who used AutoCAD, among other products), the building employs the containers’ own features in ingenious ways, including welding open the container doors to create shade fins and replacing them with panels of full-height 9-foot glass.

“This is mainstreaming modernism,” says principal Travis Price, FAIA. “There’s nothing new about building with shipping containers, but now we’re doing more density, and the culture is ready for it. Everyone dreams about having one of these California-modern glass houses, but now you can actually have that as your townhouse, apartment, or condo. It’s the best thing since brick!”

Despite the many things that make shipping containers attractive to designers, they are not without their challenges. “You have to pay attention to where the strengths of the box lie, and if you make any interventions to that box, you have to make sure you put the strength back with reinforcing steel,” Burke says. “All the structural strength is in the floor and the corner columns. People should consider hiring a structural engineer to help with that.”

The units need to be insulated, heated, and cooled, and installing those elements takes up space and requires some creative thinking because there is little wiggle room for hiding mechanical systems. Municipal zoning codes can also be a problem.

“If you are not willing to become hands-on and almost have it done as a self-built project, then the cost is not worth the challenge,” says Garcia Saxe. “If, however, you want to take charge of the construction of your home and reducing costs, then by all means, explore this possibility.”

Living in a shipping container home can be an adjustment for those used to larger houses. For Burke, however, the constrained space gives him a sense of security—the kind of enclosure and feeling of shelter that is often advocated by feng-shui practitioners. Burke calls himself a “claustrophile,” using a term associated with well-known small-house advocate Jay Shafer.

“I like being in a cozy environment; it helps me breathe easier,” Burke says. “When I need the open space, the whole world is out there.”

This blog originally appeared on lineshapespace.com/shipping-container-home.

Filed Under: Industrial automation