NASA researchers are spending at least the next six months poring over data from a recent test that involved sending volcanic ash through an airplane engine.

Read more: NASA Studying Volcanic Ash Engine Test Results

According to the U.S. Geological Survey more than 80 commercial aircraft encountered potentially hazardous volcanic ash in flight and at airports from 1993-2008. That was before the big 2010 volcanic eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland which disrupted hundreds of flight in Europe and the lives of about 10 million airline passengers over six days.

Credits: NASA Goddard

“The primary issue is that volcanic ash forms glass in the hot sections of some engines,” said John Lekki, NASA Vehicle Integrated Propulsion Research (VIPR) Principal Investigator, based at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. “This clogs cooling holes and chokes off flow within the engine which can eventually lead to an engine power loss. It is very erosive, which causes damage to compressor blades and other parts in the engine.”

The 2010 volcanic eruption came at the same time that NASA was looking at developing engine health management systems and smart sensors for next generation commercial aircraft engines.

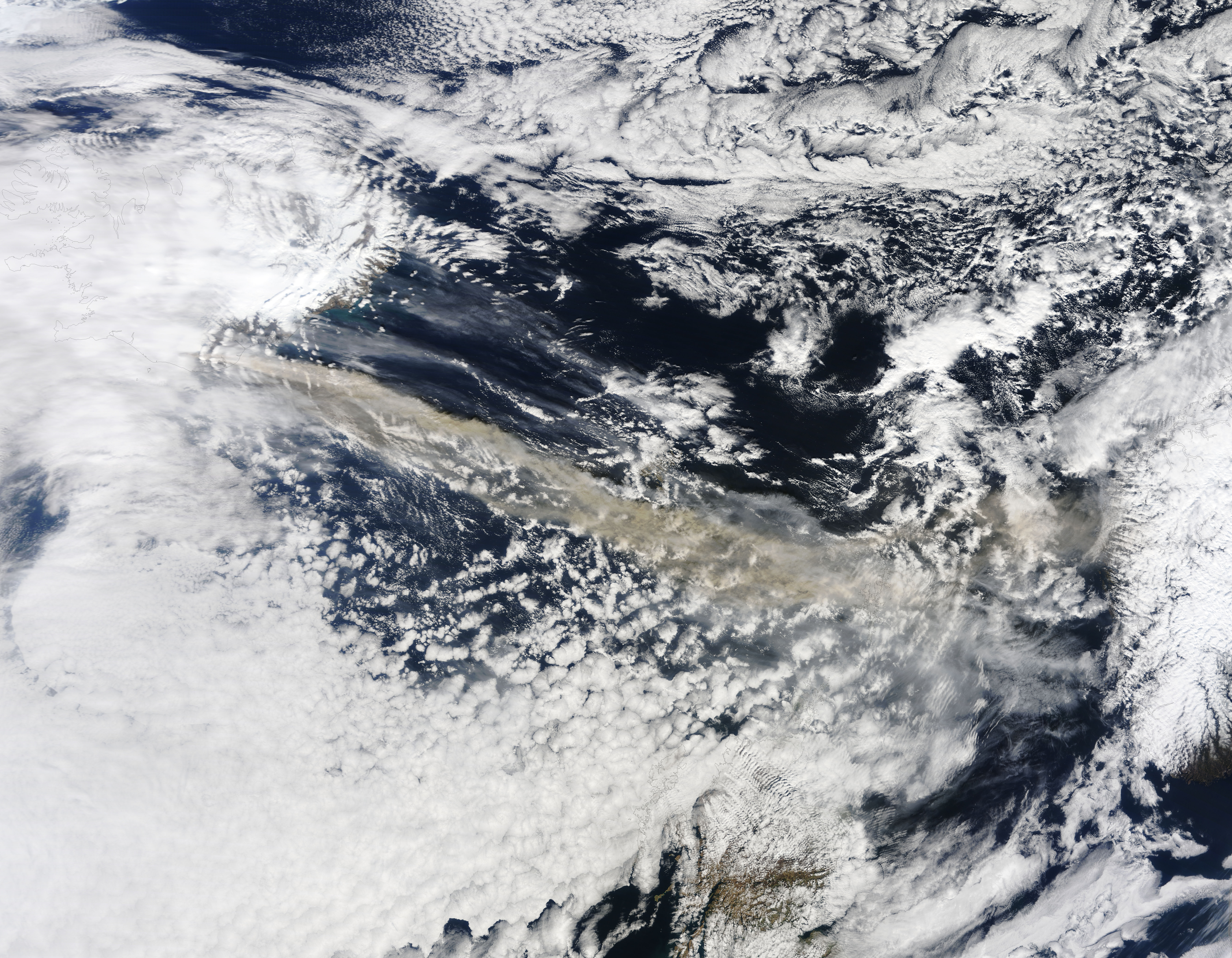

The above photo shows the ash plume (the brown streak) from the big 2010 volcanic eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, which contributed to airline disruptions in Europe for almost a week.

Credits: NASA Armstrong

So NASA partnered with other government agencies and industry, including the Federal Aviation Administration, the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls Royce Liberty Works, General Electric Aviation and Boeing Research & Technology, to conduct the series of VIPR engine tests – ending with the one in 2015 that actually simulated volcanic ash ingestion.

The Air Force provided the plane, a C-17 cargo transport, and two F117 engines that had been slated for retirement, but were overhauled to like new before the test. The F117 engine is a military version of a commercial Pratt & Whitney engine that is used on the Boeing 757.

The volcanic ash distribution spider, shown above in the inlet of the engine while running, was used to send the ultra-fine particles of ash through the engine.

The first VIPR test on the engine, heavily instrumented with sensors, happened in 2011 at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center/Edwards Air Force Base in California. It established engine and sensor performance baselines. The second test, in early 2013, used cereal and crayons, material that wouldn’t harm the engines, to verify that the sensors could detect tiny bits of debris. That test established the sensitivity of the sensors.

In the above photo, oil smoke billows from the right inboard engine of the C-17 while a probe collects emissions data during 2011 VIPR engine health monitoring tests

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense