Technicians inside a clean room at NASA’s Langley Research Center work on the SAGE III instrument, preparing it to ship to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center for launch to the International Space Station. The ozone- and aerosol-measuring instrument is the latest in a long line of atmospheric science experiments designed at NASA Langley. Credits: NASA/David C. Bowman

An autonomous, Earth-observing, ozone-measuring instrument is taking its first steps toward a new home in space.

Thursday evening, the Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment III on the International Space Station, or SAGE III on ISS, rolled out of the gates at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, aboard a specially outfitted delivery truck.

It traveled south toward NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where it is scheduled to blast into orbit next year aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

SAGE III has an important job to do. The project will give NASA a new way to monitor Earth’s protective ozone layer and document its ongoing recovery.

The thin layer of ozone in the upper troposphere and stratosphere acts as a chemical shield, defending life on the planet against the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. SAGE III will help scientists check the layer’s health, which has shown signs of improving since 1987’s Montreal Protocol. That international agreement called for a ban on ozone-eating chlorofluorocarbons.

Painstakingly updated, assembled and tested over six years at NASA Langley, SAGE III is now ready to go to work verifying that recovery — and watching for new problems on the horizon.

“This is a big milestone,” said NASA Langley’s Jonathan Chrone, who serves as launch site lead for the project. “Our team has been working very, very diligently to get the payload ready to ship. The team has put a lot of time into it and this is that final push to get it ready to fly.”

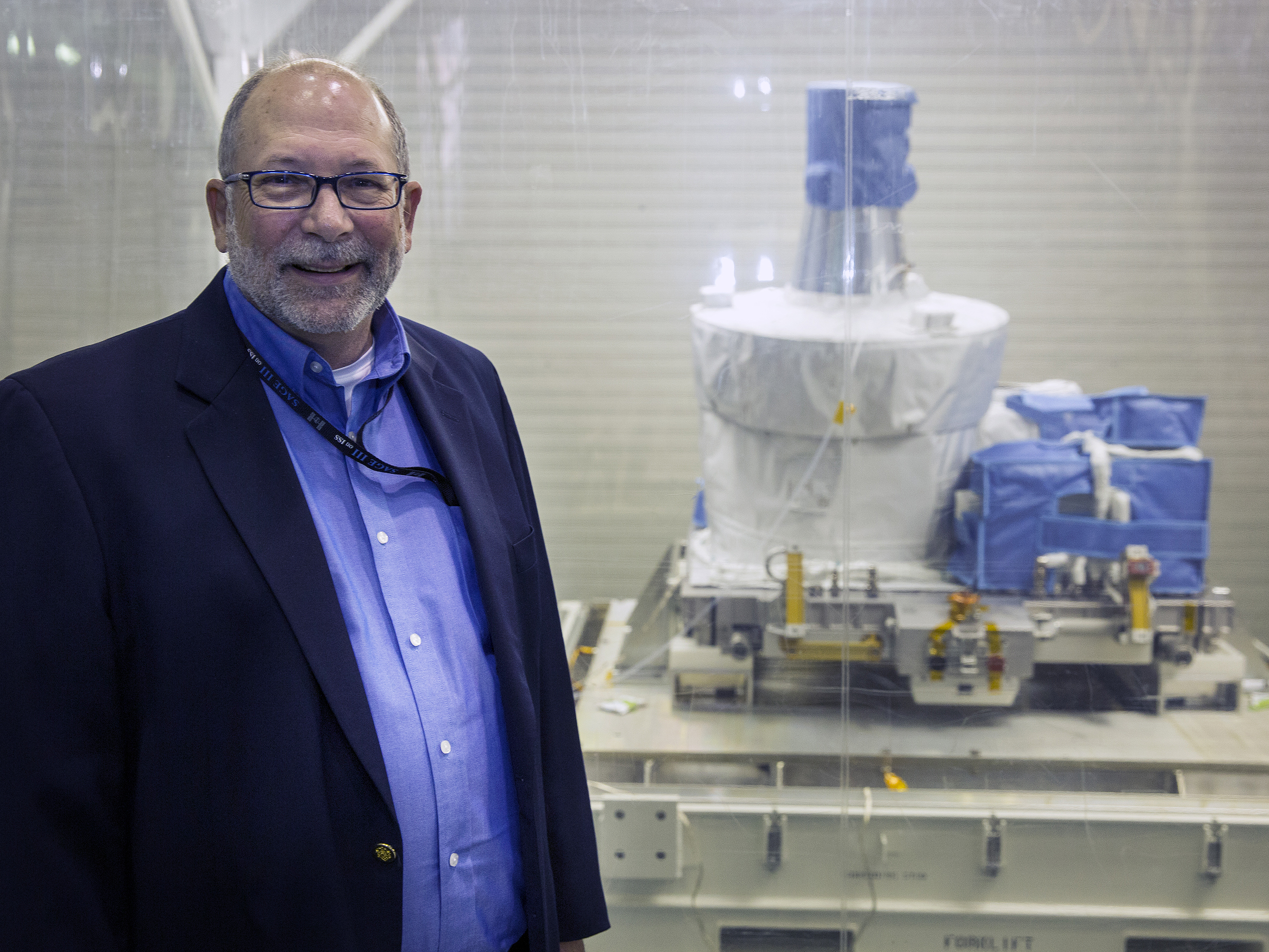

Michael Cisewski, project manager for SAGE III, said he was proud of how NASA Langley pulled together to get the instrument ready for departure.

Michael Cisewski, project manager for SAGE III, is proud of the work his team did to the instrument ready to fly. “Our team worked two shifts per day, Saturdays, and an occasional Sunday to maintain our schedule and ensure we would catch our ride to the ISS on Space X,” he said. Credits: NASA/David C. Bowman

“Our team worked two shifts per day, Saturdays, and an occasional Sunday to maintain our schedule and ensure we would catch our ride to the ISS on SpaceX,” he said. “Our team, with outstanding support from across the center, was up to the task. Delivering on our commitments today is part of the center’s culture and our team demonstrated that we can still do it.”

Extending a legacy

In one sense, SAGE III is brand new. Never before has this type of instrument been mounted on the International Space Station. The orbital path of the space station will make the instrument’s readings of ozone, water vapor and aerosols all the more valuable.

In another sense, though, SAGE III simply continues work started 40 years ago. With this mission, NASA revives and refines a tried-and-true method of atmospheric measurement that’s been dormant for nearly a decade.

SAGE III is the newest member of a high-achieving family of atmospheric science tools developed at NASA Langley.

In 1975, the Stratospheric Aerosol Measurement, or SAM, experiment was conducted on orbit as part of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the Apollo mission’s final flight.

SAM, the first experiment of its kind conducted from space, proved the value of a technique called occultation. Through that method, scientists identify components of the air by studying sunlight as it beams through the upper edges of atmosphere and comparing it to light coming straight from the sun, with no atmosphere in between.

SAM’s success paved the way for a series of satellite instruments that used the technique to measure ozone and tiny particles — called aerosols — in the atmosphere. The last of that series, SAGE III-Meteor-3M, ended service in March 2006.

New links in a data chain

The new version of the SAGE instrument is equipped with powerful tools. The instrument uses charge coupled device array detectors that, together, act as a sophisticated camera. Also, it is outfitted with a contamination-monitoring package that measures the amount of dust and fumes floating near the space station. If levels get too high, the instrument can shut itself down to protect its sensitive optics.

Most importantly, though, the new SAGE will reopen what’s been an incredibly useful data stream.

Information gathered by the SAGE family of instruments helped convince the world to embrace the Montreal Protocol nearly three decades ago. “It was that SAGE data that helped bring it together, part of what alerted the world that we were losing ozone and that it’s being depleted,” said SAGE III Mission Operations Manager Brooke Thornton. “It’s the gold standard of monitoring ozone.”

The long period of SAGE observations makes them particularly useful and the technique they employ is especially trustworthy, said Joseph Zawodny, SAGE III project scientist.

“A lot of the variability that causes drift in the measurement is removed by the occultation technique,” Zawodny said. “It’s really powerful. Once we get up there, with a couple of years of measurements under our belt, we’ll have a good idea of where the ozone is globally and be able to put together a pattern.”

Trouble shooting

Getting SAGE III ready for space was challenging — even when things worked exactly as expected.

The core of the SAGE system was developed by NASA Langley and built by Ball Aerospace & Technology Corp. in the 1990s, at the same time as that of the SAGE III-Meteor-3M. Originally, plans called for SAGE III to be mounted on the space station around 2001, but those plans were put on hold.

The main part of the instrument was safely packed away in storage for more than a decade. When NASA decided to re-ignite the project six years ago, lots of updating and revamping was needed.

Brooke Thornton, mission operations manager for SAGE III, poses inside NASA Langley’s Flight Mission Support Center where Thornton and her team will send commands to the instrument once it’s mounted on the International Space Station. “I’m very eager to see this on orbit,” she said. “I’ve never gone through one single mission through all the phases and finally to launch.” Credits: NASA/David C. Bowman

The SAGE team also needed to reconnect with the project’s international partners. For example, the European Space Agency and Italian companies Thales Alenia Space and Compagnia Generale per lo Spazio provided a key element called the Hexapod Pointing System. It automatically adjusts the instrument to ensure that it points at the correct angle for the measurements being taken.

While the project was on hold, the hexapod was stored in Italy. When engineers there pulled the hexapod out and tested it, they discovered upgrades were needed. The team there worked diligently to complete them on schedule, then shipped the hexapod to NASA Langley early this year.

About that same time, the team hit a snag.

“Just as they were about to deliver it, we found out there was an issue with it rebooting at high temperatures,” Thornton said. “We would probably have to have our pointing system power down for the majority of our mission. That was a huge issue.”

Software engineers at NASA Langley wasted no time attacking the problem, Thornton said.

“They did an amazing job of coming up with a whole new way of operating the payload, in the event that we had to turn off the hexapod,” Thornton said. “It was amazing that, in weeks, they figured out how to modify two subsystems, developed the code, tested it, certified it and took one of the biggest risks that our project had faced and came up with a very good solution very quickly.”

Protecting the planet

SAGE III was built to watch out for atmospheric threats to a healthy planet.

“You’ve got to care about ozone,” Zawodny said, explaining the mission’s significance. “We’ve got to take care of that layer.”

Defending ozone means defending Earth’s habitability. “When you look at places we could go in the solar system, there’s really no place like home,” he said. Earth has a magnetic field that protects us from the charged particles pouring in from the cosmos. It also has an atmosphere that’s not too thin, not too thick — perfect for life as we know it.

“Then, we’ve also got an ozone layer that protects us from ultraviolet light, so we don’t die from skin cancer, so our crops don’t wither in the fields,” Zawodny said.

“This planet is unique, so we’ve got to take care of it.”

- For an overview of the SAGE III project, take a look at this video.

- For a look at how earlier incarnations of SAGE led to the current version, view this video.

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense