Edited By Leslie Langnau, Managing Editor

Hill-climb racing is a branch of motorsport racing in which drivers compete against the clock on an uphill road. ETA Srl is a skilled research and testing center. Incorporated back in 1987, ETA has successfully assisted firms from the automotive, energy and mechanical industries, in a variety of projects. One of the more interesting projects was PICCHIO, an Italian race and road car producer, whose race cars compete and often win in hill-climbing races.

Niche-market hill-climbing race cars from Italy’s PICCHIO are designed using LMS Virtual.Lab Motion to handle uphill acceleration dynamics.

The first hill-climb race took place in Colorado, USA back in 1916, under the name of “Pikes Peak International Hill-climb competition.” In this particular competition, the vehicles race on a properly secured, 20 km common public road section, starting from an altitude of 2900 m and climbing up to 3300 m.

When a race vehicle curves on a classic plane curve, as in a Formula 1 circuit for example, loads on the vehicle wheels are distributed: a big load on the external front tire, a low load on the internal front tire, while the rear axle remains balanced. Due to the high slope and road banking during an uphill turn, the vehicle’s balances and loads drastically change. As a result, the internal wheel will frequently have a very low vertical load and sometimes does not touch the road at all. This creates issues for the pilot such as undesired vibration effects, excessive increase of the pitch of the car in front suspension and loss of adherence during acceleration.

Multi-body simulation to study car performance

The need for technical solutions to the control requirements for such race cars prompted the implementation of a contractive scheme. This configuration for the front suspension is called “opposite springs.”

To get a better understanding of the hill-climb acceleration dynamics and to simulate the vehicle model, ETA decided to employ LMS Virtual.Lab Motion, a LMS 3D multi-body simulation tool. The engineers used this program to model two steps:

- Create a physical model of the front suspension on the vertical direction only, to better understand the mechanism

- Create a detailed multibody model of the vehicle running on a cornering section of the road obtained by the telemetry

Simulation of a race car on a typical hill-climb race track with LMS Virtual.Lab Motion.

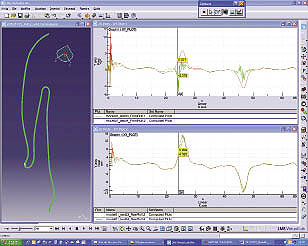

Dynamic analysis of the damping and suspension system.

Engineers used CAD inputs to make the complete model of the vehicle and to create a helical track (obtained by GPS data and measurements) where the vehicle virtually “races” in LMS Virtual.Lab Motion. The idea was to observe how the vehicle reacted to critical uphill curved track stretches and carry out dynamic analysis of the damping and suspension system.

The simulation confirmed that there is a general loss of traction capabilities and a difference between the heights of the front axle extremes. This means that one of the two tires is less in contact with the ground, worsening the vehicle’s overall performances.

The engineers found the solution for the problem by integrating the contractive device, consisting of an additional spring in the damper system to push the internal tire down to the ground. The device was also designed to achieve easy suspension set-ups during racing, such as preload adjustability of the main and extension springs, replacement of the springs, bulk space and lightness.

The design process involved not only parametric variations between contractive and normal suspension, but also model variations. For instance, the non-contractive solution implemented a stroke-end device with very high stiffness value that allowed evaluating and selecting the most promising solutions, and minimizing the experimental activity.

The tests were carried out on the track with competition testing. With respect to the car in the previous set-up configuration, the results confirmed concrete performance improvements.

The decision to go with LMS simulation tools was not taken lightly. During benchmarking, pros and cons of a number of simulation software were weighed out. Ultimately, LMS Virtual.Lab was chosen because it allowed the import of the pre-existing full CAD vehicle multi-body model and had a wide application scope and versatility.

“While simulation with other software would have required us to rebuild the race car model from scratch, LMS Virtual.Lab let us simply import the entire model in the software frame, sparing us from time-consuming individual data import,” said Engineer Pierluigi Antonini, from the Test &Simulation division-ETA Srl.

ETA still remains happy with its choice. Before LMS Virtual.Lab was chosen, the development process was one-way. Once a design was approved by the development division and reproduced by simulation, it was impossible to make any modifications on the model.

“To modify any aspect of the system’s design, we had to start the simulation again from scratch. This created subsequent project delays. But now the process is a circular one; the virtual model can always be modified by the test and simulation division if requested,” continued Antonini.

“We also appreciate how LMS Virtual.Lab Motion cuts down our development time by one-third and allows us to increase the number of models. Back in 2004, it took us and PICCHIO nine months to get a new vehicle model on the race track. In 2010, we were able to create a new race car in five months and PICCHIO won its first race two months later,” concluded Antonini.

LMS North America

www.lmsintl.com

Filed Under: Uncategorized

Tell Us What You Think!