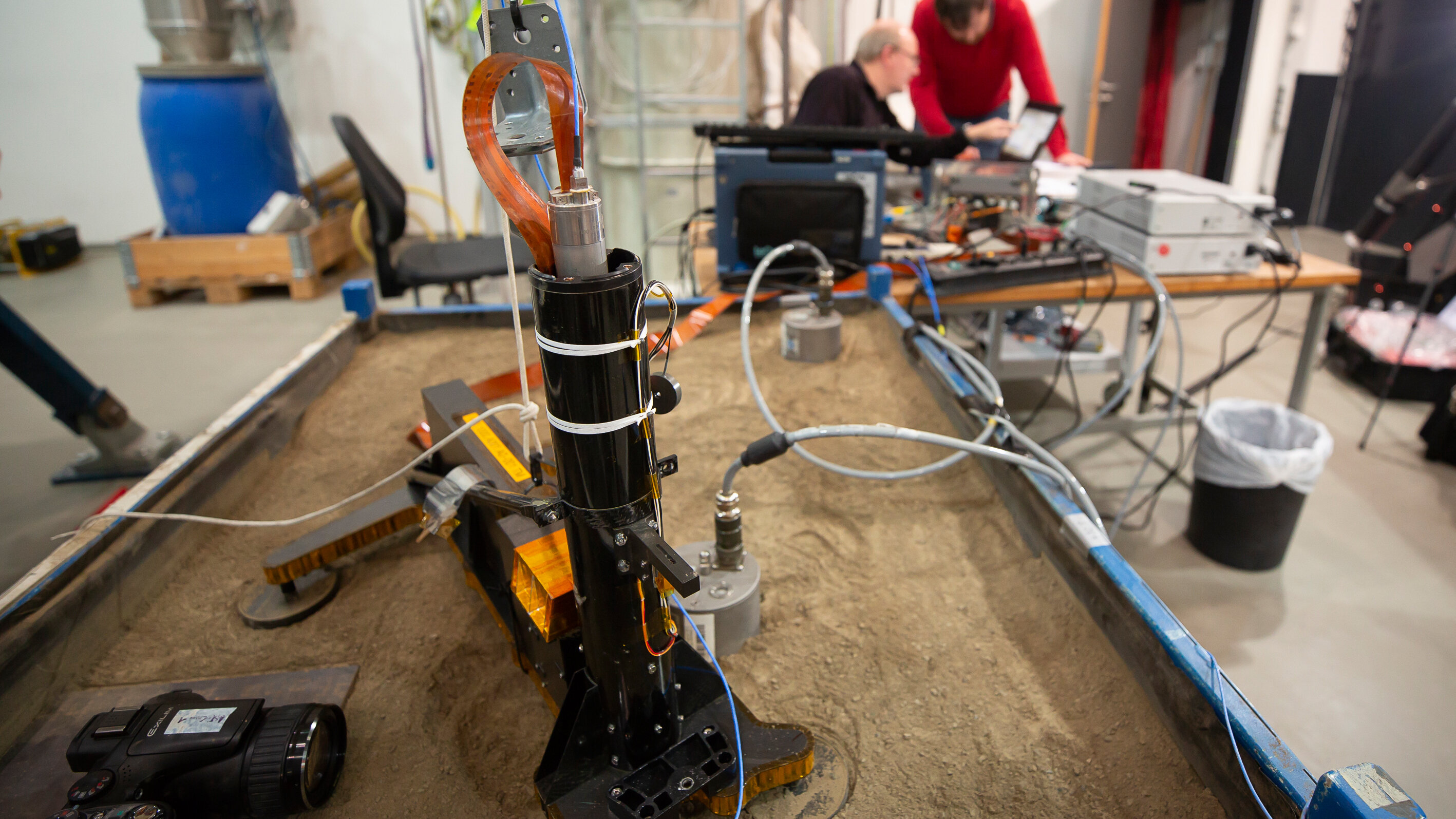

A blue box, a cubic metre of Mars-like sand, a rock, a fully-functional model of the Mars ‘Mole’ and a seismometer – these are the main components with which the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) is simulating the current situation on Mars. After its first hammering operation on 28 February 2019, the DLR Heat and Physical Properties Package (HP³), the Mars Mole, was only able to drive itself about 30 centimetres into the Martian subsurface. DLR planetary researchers and engineers are now analysing how this could have happened and looking into what measures could be taken to remedy the situation. “We are investigating and testing various possible scenarios to find out what led to the ‘Mole’ stopping,” explains Torben Wippermann, Test Leader at the DLR Institute of Space Systems in Bremen. The basis for the scientists’ work: some images, temperature data, data from the radiometer and recordings made by the French Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) during a brief hammering test conducted on 26 March 2019.

When the NASA InSight lander arrived on the Martian surface, everything looked even better than expected. Although the lander’s camera showed numerous rocks some distance away, the immediate surroundings were free of rocks and debris. The reason why the ‘Mole’ hammered its way quickly into the ground after being placed on the surface of Mars and was then unable to continue its progress is now being diagnosed remotely. “There are various possible explanations, to which we will have to react differently,” says Matthias Grott, a planetary researcher and the HP³ Project Scientist. A possible explanation is that the ‘Mole’ has created a cavity around itself and is no longer sufficiently constrained by the friction between its body and the surrounding sand.

Another type of sand

In Bremen, DLR is now experimenting with a different type of sand: “Until now, our tests have been conducted using a Mars-like sand that is not very cohesive,” explains Wippermann. This sand was used during earlier tests in which the ‘Mole’ hammered its way down a five-metre column in preparation for the mission. Now, the Mole’s ground model will be tested in a box of sand that compacts quickly and in which cavities can be created by the hammering process. During some of the test runs, the researchers will also place a rock with a diameter of about 10 centimetres in the sand. Such an obstacle in the subsurface could also be the reason why the HP³ instrument has stopped penetrating further. In all experiments, a seismometer listens to the activity of the Earth-based ‘Mole’. During the short ‘diagnostic’ hammering on Mars, SEIS recorded vibrations to learn more about the Mole’s impact mechanism. Comparisons between the data obtained on Mars and the Earth-based tests help the researchers more closely understand the real-life situation. “Ideally, we will be able to reconstruct the processes on Mars as accurately as possible.”

the HP3 experiDLR engineer Torben Wippermann with mental set-up. Credit: DLR German Aerospace Center

‘Moles’ on Earth as guinea pigs

The next steps will follow once the scientists know what caused the progress of the ‘Mole’ to come to a halt on 28 February 2019. Possible measures to allow the instrument to hammer further into the ground must then be meticulously tested and analysed on Earth. For this reason, a replica of the HP3 instrument has been shipped to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. There, the DLR researchers’ findings can be used to test the interaction of the ‘Mole’, the support structure and the robotic arm to determine whether, for example, lifting or moving the external structure is the correct solution. “I think that it will be a few weeks before any further actions are carried out on Mars,” says Grott. The break in activities for the Mars Mole will only come to an end once a solution has been found for the Earth-based ‘Moles’.

DLR engineer Torben Wippermann with the HP3 experimental set-up. Credit: DLR German Aerospace Center

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense