Ben Reytblat, 3DMonstr’s CEO, poses with his creation. All image credit: 3DMonstr.

Sporting a quad-extruder, liquid-cooled print head, a working volume of up to eight cubic feet, and industrial-grade quality at prosumer prices, 3DMonstr’s 3D printers occupy a unique space within the market.

Ben Reytblat, 3DMonstr’s CEO and lead designer of the T-Rex 3D series is as unique as the printers he creates. The son of a Russian physicist, inventor, and amateur rocket scientist, Reytblat is a renaissance geek, equally comfortable piloting a CNC milling machine, a software development suite, or a sailboat.

In designing his printer, Reytblat set out to fix many of the big and small deficiencies he noted in the machines already on the market, something that he quite frankly admits was a formidable, perhaps even “Monstrous” task.

He is also quick to point out that, despite the delays it caused, re-thinking every aspect of 3D printing resulted in a much better product, and taught him some valuable lessons he’ll be applying to the next generation of 3DMonstr products. In this exclusive interview with PD&D, Reytblat generously agreed to share some of those hard-won insights with our readers.

PD&D: What were the design goals which drove the development of the T-Rex 3D series of 3D printers?

Reytblat: We wanted to build a machine that was two steps beyond anything on the market at the time. So it had to be really large (up to 8 cubic feet of build volume); it had to have more extruders than anyone else at the time; and it had to be able to work with more materials than anyone else at the time. We think we’ve succeeded in doing just that. In some areas, we’ve even exceeded our own expectations. For example, the multi-zone heated bed on our printers is much more efficient that anyone else’s on the market. Because you can control each of the 6 x 6” zones individually, you don’t need to heat the universe with a full 960 watts of power, saving energy and reducing costs of operations.

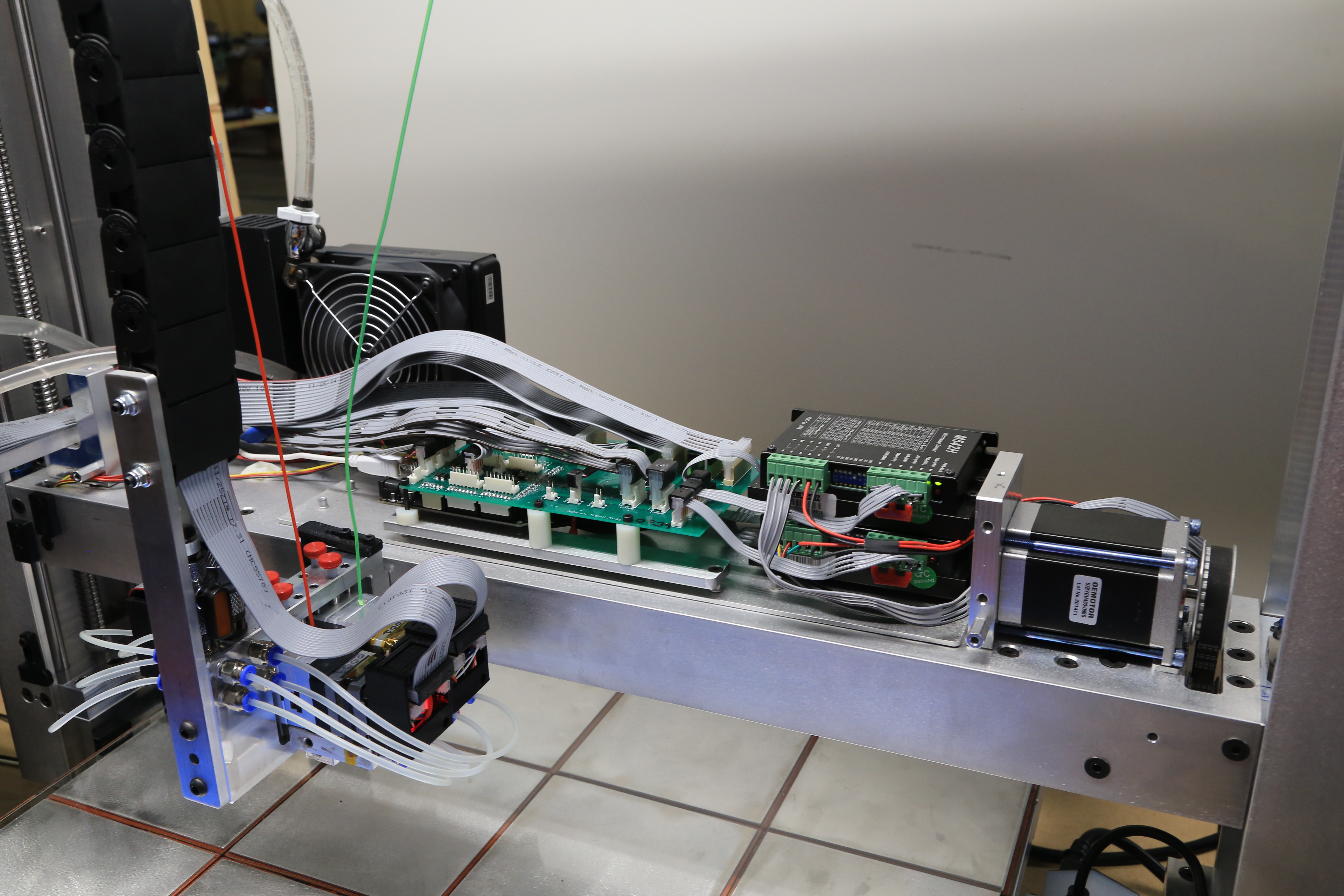

The printer’s water-cooled quad-extruder print head is designed to deliver precise, repeatable, high-resolution prints using a wide range of materials.

PD&D: The extruder mechanism is one of the most unique aspects of your machine. What does it offer the end user and what were some of the challenges involved with designing it?

Reytblat: There are two major advances embodied in our extruders: a very precise drive mechanism we call our GentleDrive, and a much more sophisticated thermal system which uses liquid cooling and components made out of titanium to manage the temperature within the extruder. Combined, these technologies give excellent print quality across a very large range of materials, from PLA to Nylon, from ABS to Polycarb, from HIPS to paraffin wax. Yes, our machines can print with a specially manufactured paraffin wax filament. This allows our users to go directly from a 3D model to a foundry-ready wax plug. Just print it and ship it to a foundry to be cast into metal using the old reliable lost-wax casting technology. I’m not aware of any other machine on the market that can offer that.

On top of that, our extruders are very compact and light-weight. Our entire extruder, all up, weighs in at just 310 g – less than most NEMA17 motors that are used in conventional extruders. And this allows us to mount all four of them in the space and weight limits of two extruders on any other machine I know.

PD&D: You also experimented with several different technologies for controlling the stepper motors used to drive the printer and extruders. What were the problems you encountered and how did you finally overcome them?

Reytblat: This was a long journey, and was ultimately the cause of a large portion of the delay we’ve experienced in bringing our machines to market.

Our goal was to build a machine with four extruders and with larger than usual motors (NEMA23 vs. NEMA17), so we could achieve reasonable printing speeds with a much heavier printer. From the outset, we knew this would be difficult.

At the start, we designed our machine around an existing off-the-shelf Arduino compatible micro-controller. The board was great, and the company behind it was even better. Alas, after many months of trying we had to give up on it. We couldn’t solve the problems of wiring, due to how the connectors were laid out. It was far too expensive to produce, and it just couldn’t be maintained in the field.

So the next approach we tried was to go completely in the opposite direction. We partnered up with a great little custom electronics house right here in New Jersey to design and manufacture a complete, from scratch, fully integrated custom controller that would have all the functionality we needed, including all motor drivers, all on one board. That also took many months, but in the end had to be abandoned as too ambitious.

Finally, we ended up with a combined architecture which gave us the best of both worlds. Our main controller is a large custom Shield sitting on top of a standard, off-the-shelf Arduino Mega micro-controller board. This gives us the best of both worlds: a well-known, cost-effective, reliable central processor with plenty of memory and I/O and a large-area custom board which allowed us to organize our connectors and other peripheral circuitry just the way we wanted.

In particular, it allowed us to drastically simplify and reduce the costs of all the wiring in the system, and at the same time improve our ability to support our customers for a long time to come. In the future, the modularity afforded by this approach will enable us to upgrade the electronics over the years with excellent backward compatibility and easy field installation. And our partner company can still make it reliably for us right here in New Jersey.

3DMonstr printers undergoing assembly at the company’s main plant, located in West Windsor, N.J.

PD&D: Your extruder’s design enables it to handle a very wide range of materials, but you’ve already hinted at developing other extruders which will allow your machines to print even more exotic stuff. Can you comment on what types of materials you’re aiming for and when you expect to roll out those capabilities?

Reytblat: We have very high ambitions. We think we’ve figured out how to 3D print with metal and with glass at a much lower cost than possible today. We’ve already filed for a patent on the former, and are working on the patent application on the latter. If we’re successful in developing this technology, I think it will revolutionize the industry by reducing the cost of metal and glass 3D printing to a level unheard of before. Stay tuned!

PD&D: There are rumors that you originally decided to design a 3D printer to help you build a new type of rocket engine. Are those rumors true? And will any of the new extruders you’ll be working on be related to your rocketry venture?

Reytblat: That is indeed how we started on this journey. The metal extruder is exactly what needed to do that. However, as so often happens, the journey became the goal in and of itself. And so these days rocketry is a hobby, and 3D printing is the main focus of what we do. When the metal extruder is done, I’ll certainly try printing a rocket engine. But I think 3D printing is now in my blood, so we’ll stay focused on it for a very long time – it’s just too much fun! And in particular, the approach we’re taking to it, enabling people to print things they can’t print any other way, is very satisfying. I really enjoy coming to work every day and taking on the challenges of engineering and manufacturing. And I love our crew!

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2016 print issue of Product Design & Development.

Filed Under: 3D printing • additive • stereolithography, Industrial automation