NASA’s Curiosity rover launched November 26, 2011, toward Mars, landing on the Red Planet August 6, 2012, in the 96-mi-wide Gale Crater. Unlike its older counterpart Opportunity, Curiosity is still on talking terms with Earth, and after more than a year of exploring Mars’ Vera Rubin Ridge, it has moved on to another site.

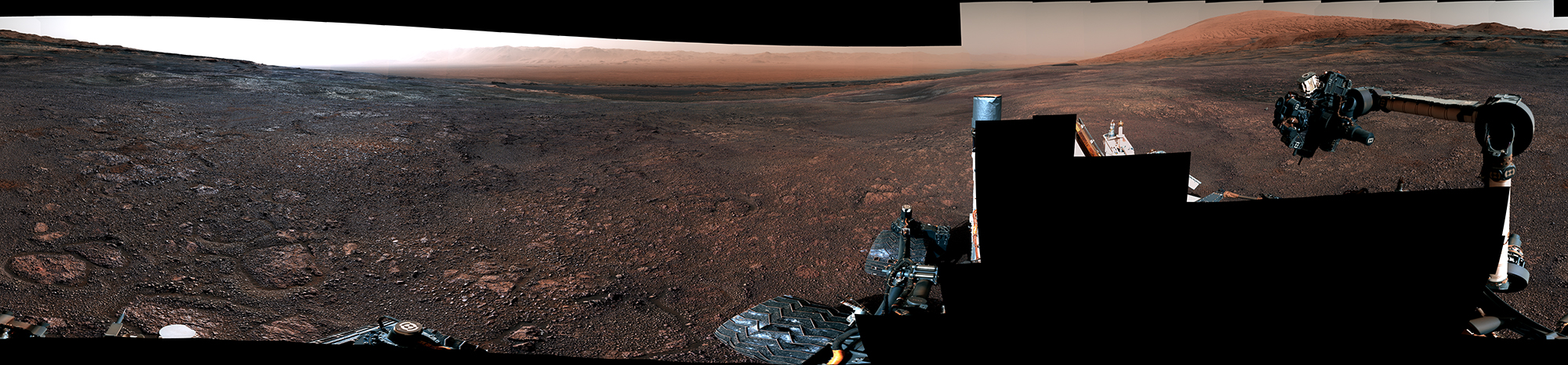

But the rover isn’t transitioning to its new spot without a little something for the public to enjoy. Curiosity took a panorama of its final drill site on the ridge, nicknamed “Rock Hall,” December 19, and we all can view it in a 360-degree video.

Interestingly, viewers can also spot Curiosity’s next target in the video, a region on the bottom of the Gale Crater known as the “clay-bearing unit,” named “Glen Torridon.”

Although the rover spent a good deal of time at Mars’ Vera Rubin Ridge, the team is still trying to understand why the area has evaded erosion compared to its surroundings. “But the rover’s investigation did find that the rocks of the ridge formed as sediment settled in an ancient lake, similar to rock layers below the ridge,” according to NASA.

A NASA orbiter is also focused on this particular region, and it was able to pick up a signal from the mineral hematite, which often forms in water. Curiosity was able to verify these claims during its Vera Rubin Ridge days, confirming hematite was present, along with other ancient water signs, such as crystals. Researchers also noticed that the rover’s mapping of mineral signatures didn’t always sync up with the orbiter’s view from space.

“The whole traverse is helping us understand all the factors that influence how our orbiters see Mars,” says Abigail Fraeman, Curiosity science team member of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “Looking up close with a rover allowed us to find a lot more of these hematite signatures. It shows how orbiter and rover science complement one another.”

Figure 1: Panorama image of Curiosity’s last dig site at Mars’ Vera Rubin Ridge. (Image Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

While exploring the ridge, Curiosity experienced “a roller-coaster year,” according to NASA.

In May 2018, the rover’s drill was able to collect samples once again, but was short lived when it went up against some hard Martian rocks. However, the team was still able to collect the ridge’s three major rock types.

Engineers built two computers for Curiosity, just in case one ran into issues, and their foresight paid off. While one computer experienced a memory issue, the team was able to switch to the rover’s second computer.

Issues aside, Curiosity’s next sights at Glen Torridon are set on a clay mineral known as phyllosilicates, which also forms in water. The team hopes the new drill site can shed more light on Gale Crater’s ancient lakes.

“In addition to indicating a previously wet environment, clay minerals are known to trap and preserve organic molecules,” says Curiosity Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada of JPL. “That makes this area especially promising, and the team is already surveying the area for its next drill site.”

Organic minerals (the building blocks of life) and clay minerals have both been found by the rover within Mars’ rocks. “If both water and organic molecules were present when the rocks formed, the clay-bearing unit may be another example of a habitable environment on ancient Mars—a place capable of supporting life, if it ever existed,” according to NASA.

As we look forward to the spacecraft’s next endeavors, enjoy the 360-video below of Mars’ Vera Rubin Ridge.

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense