Camille Eddy • Robotics and software engineer | TIMBER IT Consulting

During the first Black History Month she recalls as a little girl, robotics and software engineer Camille Eddy got to learn of NASA astronaut (and engineer and physician) Mae Jemison. Inspired by Jemison’s story as the first black female astronaut and work in space during NASA’s 1992 STS-47 mission, Eddy decided she wanted to be an astronaut as well. So Eddy’s mother assigned her a small research assignment to determine what it takes: “I found out that astronaut candidates must first be scientists, doctors, or engineers … and I wanted to go into engineering. It was then that my mother and I began thinking of the classes and coursework to get me ready for that path.”

Camille Eddy presenting.

Camille Eddy as a child with her sister.

Eddy continues: “In my high school freshman year, we moved to Boise, Idaho. Within two months, my mom had connected us with the Engineering College at Boise State University. During one special event at the school, my sister and I got to meet former astronaut Barbara Morgan who had just arrived at Boise State as a distinguished educator in residence. At that same event, presenters from the Engineering College explained to us high schoolers the different fields of engineering.”

At the close of the event, Eddy, her mother, and her sister stayed to get Barbara Morgan’s autograph. “But my mom lingered to ask Barbara a lot of pointed questions such as, ‘Can my daughter really be an astronaut?’ and that sort of thing. Ultimately Barbara Morgan stayed with us for three or so hours after the event — I swear a very long time,” Eddy laughs recalling the evening. “We even went to her office that night, and she showed us some plant seeds that had been to space … it was incredible.”

Barbara Morgan would go on to mentor Camille Eddy for the next six years, making both the young woman and her family increasingly comfortable with her career choice. Eddy benefitted greatly from the instrumental relationship. She regularly saw Morgan at events around town, and her exposure to Morgan continued through various day and residential camps at Boise State.

After completion of high school, Eddy started at Boise State as a mechanical engineering student. There, Morgan invited Eddy to serve on a panel to help facilitate educational exchanges between astronauts in space and Boise State students. That program ultimately included a BSU Space Symposium coordinated with the International Space Station. This is where the mentorship really took flight so to speak — as Morgan served as a liaison between the students and NASA.

“We had to have meetings with the NASA educational team; we had to learn how to write proposals. Morgan worked with me with me to write an education and public outreach (EPO) plan. These are educational scripts that astronauts present as videos from space — to provide engaging technical sessions to students and the public. Our EPO presentation was on Newton’s third law.” On the day of the BSU Space Symposium, all of the students got coaching … but Eddy was brand new to public speaking. Here, Morgan coached Eddy on how to present on stage and speak clearly — which ultimately served as yet more meaningful mentoring.

The next year, Eddy became team leader for a research project called the Microgravity Undergraduate Research Experience, coordinated with NASA to teach undergraduate students how to write business proposals to NASA standards and then execute a research project if contracted. Eddy’s six-student team focused on space tooling. “With Barbara’s help, we wrote a 40-page proposal to NASA. Every night we worked until 10 pm on this project. The last night, Barbara stayed with us until 2 am just going over the project proposal line by line to instruct us on how to make our proposal fit the standards of NASA.

Camille Eddy pictured with Barbara Morgan

After the proposal was approved, Eddy’s team had to build the tool. “We had to write a safety document for the tool and then test the finished tool at the NASA Johnson Space Center. We then had to appear in front of a large panel of astronauts and testing and educational professionals and present our document. Because of all the coaching we got from Barbara and all the steps we’d taken on engineering and documenting the tool’s function and adherence to design parameters; they didn’t have any questions for us … and weren’t concerned about anything that we had done. For example, our tool allowed single-hand operation and did not have any sharp edges — just two design features required by NASA.”

Eddy remembers most fondly the help Morgan gave her on understanding team leadership.

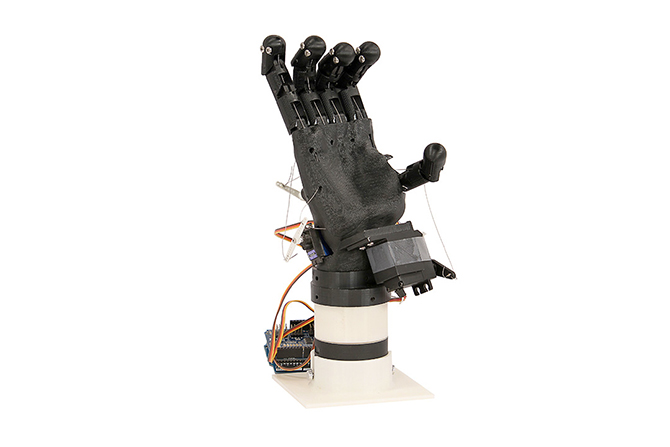

In addition, Eddy’s familiarity with standardized modes of engineering communication now helps her work on a remote team as a robotics engineer. Most of her efforts these days focus on those within the open-source Robot Operating System (ROS) — middleware that lends itself to prototyping and lets engineers plug and play robots after building custom applications to specification.

“My day-to-day work now is now on modes of building robotics from scratch … currently for a pick-and-place robot. So I start my day with reading, and working on coding in Python, C++, and XML. Particularly satisfying is addressing changing design requirements and predicting design outcomes. Our remote team communicates a lot over online chat: ‘This is what I did — does this work for you?’ and ‘I’m pushing my code to the repository; can you check it?’ and things like that. It’s quite a lot of communication, because we also have to divide up our tasks.”

“It’s not so important that we convince girls to pursue engineering. It’s about fostering environments to ensure that once they enter their careers, they remain willing to stay”

“Case in point: Our current robotic design requires some mode of gripping. Ultimately, we decided to use suction end effectors to pick up objects and move them. But how do we design this portion of the robot? What code to use in simulation for proof of concept? What about sourcing subcomponents? Such systems require careful consideration.”

For holistic design conceptualization, Eddy borrows from her experiences on a design project for HP — to build a multi-functional end effector to test printer functions. Initial prototypes were cumbersome, and the kinematics in particular proved difficult; the final iteration was streamlined, modular, and 3D printed … a simple cable-based push-pull system under digital control based on camera feedback.

When asked about ways to increase participation of young women and people of color in engineering and STEM fields, Eddy said cited inclusive workplaces as key. “It’s not so important that we convince girls to pursue engineering. It’s about fostering environments to ensure that once they enter their careers, they remain willing to stay.”

Photo of Camille Eddy • Courtesy Jonni Armani

“I myself have had been with several different companies and experienced things I liked and didn’t like. Key is ensuring people don’t feel like they need to come to work and advocate for themselves more than other people do — or work to protect themselves from certain situations. I think that’s going to take a lot more work than simply attracting girls to STEM — an inherently interesting field.”

You may also like:

Filed Under: NEWS • PROFILES • EDITORIALS, Engineering Diversity & Inclusion, Student programs