Natasha Townsend, Associate Editor

Gary Conley’s 30-year quest to manufacture a true production V-8 engine in quarter-scale almost went up in smoke…twice. Once in 2001, a foundry fire claimed all his critical molds. Later, oil smoke proved a stubborn problem during run-offs of the engine. Conley overcame the first setback with years of sheer determination. The second issue required a Sunnen expertise, MB 1660 honing machine, and abrasives.

Gary Conley holds his Stinger 609 quarter-scale engine modeled on a Viper V10.

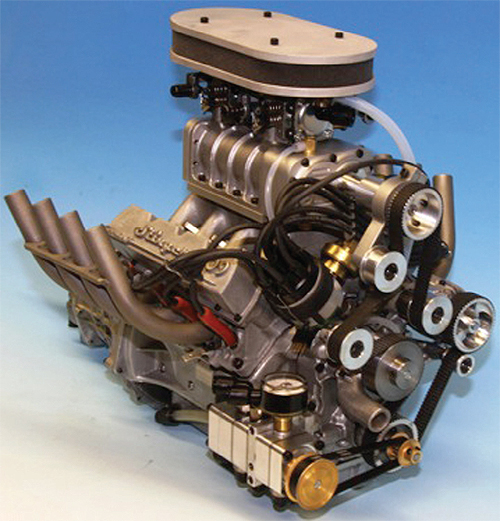

Conley’s Stinger 609, V-8 is no toy or novelty, but a serious engine built for high performance and durability. Modeled on a Viper V-10 (available in naturally aspirated or supercharged versions), the Stinger has a dry-sump, pressurized lubrication system, electronic ignition, electric starter, split main and rod bearings, steel valve guides and seats. The bore is about 1 in., with a 0.952 stroke. The crank and cam are 4140, casehardened to 20 microns deep and then ground. The engine uses freestanding, full-wet, cast-iron liners. Cosmetically, investment casting gives exceptional detail to parts cast in 356 aluminum and hardened to T6, such as the pan, heads, valve covers, crankcase and timing cover.

In 1996, Conley’s reputation led Chrysler to request that he build a quarter-scale Viper V-10. Soon after, a full-size V-10 engine arrived at his shop to be reverse engineered to the quarter-scale size. After five years of development, with the V-10 ready to go into production, disaster struck. More than $350,000 in molds and five years of time were destroyed in a foundry fire. However, Conley retained the mold masters from the V-10, and realized he had plenty of knowledge to build on. With steely determination over a period of additional years, he carefully redesigned his tooling to produce V-8 components, and thus was born the Stinger 609.

The engine has a dry‐sump, pressurized lubrication system, electronic ignition, electric starter, split main and rod bearings, and steel valve guides and seats.

According to Conley, the first units of the Stinger engine burned oil so badly they filled a room with smoke in seconds. He discovered the problem was too much oil being pushed up into the cylinders. Though he did not realize it at the time, his honed cylinder surface was too smooth.

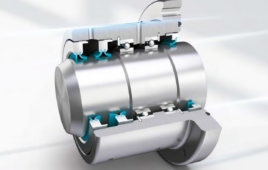

Digging deeper into the science of ring and cylinder design, he learned about the nuances of crosshatch, including the proper angle and depth required to create valleys to retain the oil. After consulting with Sunnen engine experts, Conley determined that plateau honing – a second pass with a brush or milder abrasive – removes the surface peaks left by the initial pass. It creates a surface profile that resembles a series of plateaus, providing a much greater bearing area, while maintaining the crosshatch valleys for oil retention.

Honing continues to be an important step in the creation of Conley’s quarter-scale beasts. He attributes much of his honing knowledge to Sunnen; yet, stresses he designs for longevity.

A serious engine, built for high performance. It is available in naturally aspirated or supercharged versions.

In terms of output, the normally aspirated Stinger produces about 4.5 hp, while the supercharger version hits 9.5 hp at 10,000 rpm. Today, Conley sells the engines with a test stand for collectors, or as crate motors for builders of model boats or other adult toys. He also offers the engines in a quarter-scale 1934 Ford or 1923 T-bucket roadster, and has his own 7-ft dragster.

Conley sources the parts that he doesn’t create himself, including quarter-scale spark plugs from miniature model engine builder Paul Knapp in Payson, AZ, rings from Dave McMillan at D.A.M. Good Engineering in San Jose, CA and castings from Invest Cast, Inc. in Minneapolis, MN.

Sunnen Products Co.

www.sunnen.com

Conley Engines

www.conleyprecision.com

Filed Under: Automotive, MORE INDUSTRIES

Tell Us What You Think!