In recent months, the federal government has stepped up efforts to address the crisis of opioid addiction in the U.S., including a batch of policy adjustments presented by Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell in July.

The portion of that HHS announcement that has perhaps roused the most discussion is the proposed elimination of pain management questions from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) patient satisfaction survey.

Though some healthcare providers have stumped for precisely this change, there are plenty of people out there who feel this particular adjustment of the evaluation tool creates a completely new set of risks.

“I think, frankly, that it is the wrong way to go about doing this,” says Roger Massengale, general manager of acute pain solutions at Halyard Health.

“The issue is, I believe — passionately — there are better ways to control pain that don’t involve opioids and I think what we need is better education for physicians and patients that those methods exist. I don’t think it’s widely known and understood by most healthcare providers that there are such methods and that maybe emphasizing change of clinical practice to non-opioid methods is a better way to solve the problem. Patients would ultimately use far, far fewer opioids and the addiction crisis would be diminished substantially.”

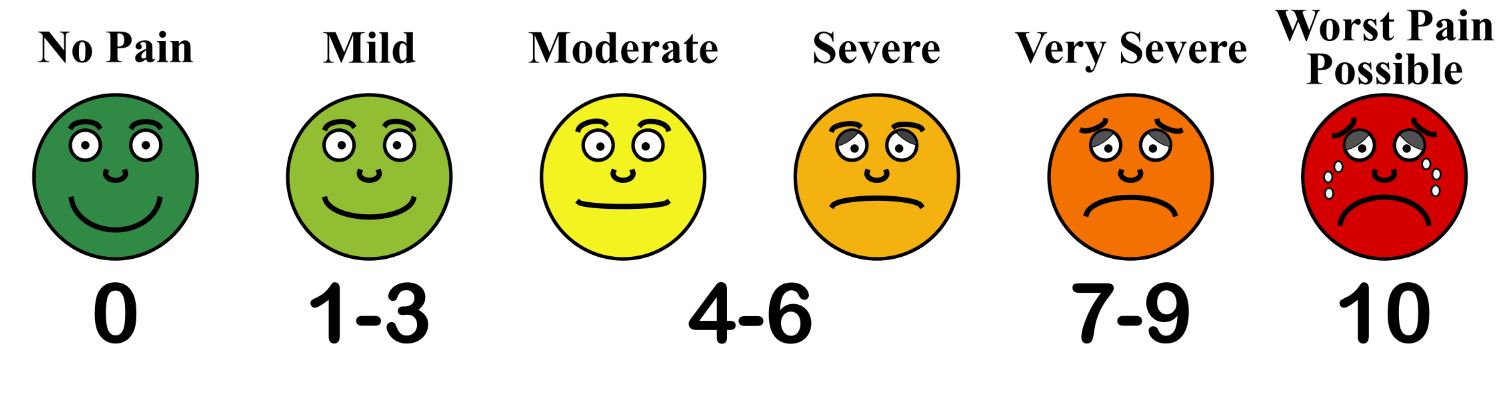

Massengale argues that multiple studies suggest the effectiveness of a facility’s pain management protocols correlates significantly with patient satisfaction levels, and stripping that component out of HCAHPS effectively leaves those very patients susceptible to an experience marked by unnecessary discomfort.

While there’s an obvious need and strong temptation to use regulatory measures to address the opioid crisis, recent history suggests that the eagerness to make adjustments often leads to unintended consequences, sometimes compounding the problem. Massengale notes that market research suggests that requirements for patients to return to their physicians for refills resulted in initial outlays of pills that far exceeded the need.

T.J. Gan, MD, MHS, FRCA, agrees that many patients are prescribed more opioids than they need. Some patients are given as many as 90 pills when they may take only a few to control their pain.

According to Gan, this surplus of medication out among the general population can itself lead to addiction.

“The problems with that is many opioids are left unused in the medicine cupboard and are potentially accessible by other family members, hence opened to abuse,” says Gan. “The solution would be to prescribe two to three days’ worth of opioids and have a script for refill if needed.”

Gan contends that it’s a mistake to disregard pain management as a factor in measuring patient satisfaction. Instead, it’s important to be proactive.

As president of the American Society of Enhanced Recovery (ASER), Gan is trying to empower patients to be active participants in finding better strategies for working through pain during recovery processes. ASER has joined with Pacira Pharmaceuticals to develop a campaign called Choices Matter, which includes an educational website and a customizable guide meant to strengthen communication between patients and doctors.

“Pain is very subjective and pain management needs to be tailored at an individual level,” Gan explains. “Good communication coupled with written instruction would go a long way to educate patients on their options of analgesia and what side effects to expect.”

Informed patients can have valuable input into the treatment regimen, which in turn heightens the possibility that they will commit to it fully.

Patients aware of the array of options available to them may even opt to bypass opioids altogether, especially with the heightened public awareness of potential pitfalls.

Massengale notes that Halyard Health offers non-narcotic pain management options, such as ON-Q, an elastomeric pump that delivers local anesthetic to the surgical site, and COOLIEF, a minimally-invasive cooled radiofrequency treatment for chronic pain.

There are other options on the market. Pacira Pharmaceuticals offers EXPAREL (bupivacaine liposome injectable suspension), a single-dose local analgesic administered during surgery that provides prolonged non-opioid postsurgical pain control.

Unfortunately, some medical reimbursement structures undervalue alternative, multimodal therapies, getting stuck on the familiar fix of a bottleful of pills. Massengale thinks this dilemma is shifting, due to the harsh realities of the opioid epidemic.

“While an opioid pill is cheap, the cost of an addicted patient in society is very expensive and extremely problematic. And I think CMS realizes that now,” he says. “It might be worth taking a look at some of these other treatment options and asking, do we have appropriate payment methods for them?”

Filed Under: Industry regulations