Built in 1938 by Ehrhardt & Sehmer, the Groussgasmaschinn is the largest gas engine ever built.

Until recently, 3D scanners could only be used indoors, under certain lighting conditions, with a steady power source, and powerful computer. They were often bulky and heavy, making them hard to maneuver while scanning. Most significantly, such scanners could only capture objects of limited sizes — something that could fit on your desk. This was the situation the team at the Luxembourg Science Center found themselves in back in 2016 when they came up with a plan: to digitally preserve one of Luxembourg’s national monuments, the “Groussgasmaschinn” or Gas Engine №11 – the world’s largest blast furnace gas engine ever built.

Built in 1938 by German manufacturing company Ehrhardt & Sehmer by order of a Franco-Belgian consortium called “Hauts-fourneaux et Aciéries de Differdange, St-Ingbert & Rumelange” (HADIR), the Groussgasmaschinn is so large it could contain an entire tennis court, and then some. It is 26 meters long, 10.5 meters wide, 6.5 meters high, weighs 1,100 tons, and could produce 11,000 horsepower, or up to 7000 kilowatts. It has four cylinders, each of which had a capacity of 3,000 liters, and an 11-meter and 150-ton flywheel, which rotated at 94 RPM. The engine was operated by 12 workers per shift, and during its lifetime (1942-1979), produced more than 6,000 kW of power from blast furnace gas (a waste product generated by the combustion of coke fuel in blast furnaces).

Located in Differdange, Luxembourg’s industrial town 27 kilometers southwest of Luxembourg City, this 1,100-ton industrial masterpiece was one of 14 other gas machines of various sizes installed in the Differdange Gas Engine Plant between 1896 and the 1940s.

The size and complexity of the object determined the scanners to be used: Artec Ray and Artec Leo.

After its shutdown in 1979, the Groussgasmaschinn remained abandoned for nearly 30 years. It came back from the brink of oblivion in 2007 when Luxembourg’s Ministry of Culture designated it as a National Monument worthy of preservation and restoration. The restoration work began five years later, in 2012. During this time, the Center developed the idea not simply to restore the gigantic engine to its best shape but also to digitally preserve it for future generations.

In 2016, they reached out to Artec 3D in Luxembourg, but even the best of the scanning technology available at the time wasn’t able to capture something this huge. Fast forward a few years, and with new 3D scanning options available, Artec was ready to scan.

“We’ve been meaning to scan this engine for a very long time, and we’re glad that the technology is finally here to help us do it. There is no other gas engine like this one, and it’s crucial to capture it in its current state,” said Nicolas Didier, President and General Manager of the Luxembourg Science Center.

“It’s the largest object we ever scanned! And much bigger than I expected,” said Vadim Zaremba, Deployment and Technical Support Engineer at Artec 3D, when he first visited the Gas Plant to assess the scope of future work in November 2020. After examining the gas engine and passing all the required security procedures in early 2021, Vadim returned to the Gas Plant with his colleague, Technical Support Specialist Raul Monteiro, and all the necessary gear.

As in most cases, the size and complexity of the object determines the scanners to be used. Artec Ray was chosen as the primary scanner for capturing the entire engine due to its ability to scan large objects from a distance with submillimeter accuracy, while the Artec Leo, a wireless, portable 3D scanner, was chosen as a second device, specifically for capturing high levels of detail from the smaller parts and sections of the engine.

While Ray silently scans the engine, Zaremba steps away for a minute or two of scanning smaller sections up close with Leo.

The plan was to first scan the engine with Ray from as many angles as possible, capture the entire object, and then go back and scan any missing, smaller, hard-to-reach sections with Leo. Because Ray was scanning at maximum resolution (point density), to save some time, the team decided to split up. Zaremba was positioning Ray at various locations, at one particular angle, 5 to 15 meters away from the engine, while Monteiro was scanning smaller sections of the engine (which weren’t in Ray’s field of view) with Leo. Then Zaremba moved on to the next spot, and Monteiro followed behind, along the same route.

One of the most challenging tasks was scanning the engine from above. To do this, the team had to climb a special bridge built in the 1940s-1950s, which features a cabin hanging 10 meters above the floor, as this was the ideal spot for scanning the engine from multiple angles. This was easier said than done. The bridge was old and unstable, and under the weight of two people plus a 3D scanner, such a foundation was not conducive to creating high-quality scans. To ensure that the scan data was flawless, Zaremba and Monteiro had to remain completely still for several minutes while the scanner did its job.

Overall, it took the team four working days to complete the project, with three to four-hour shifts of active scanning every day. The engine was scanned from 18 different angles with Artec Ray, and these were later combined in Artec Studio with 67 more scans made with Artec Leo. The final size of the project came to 186 GB in total, with 170 GB of Leo scans and 16 GB of Ray scans.

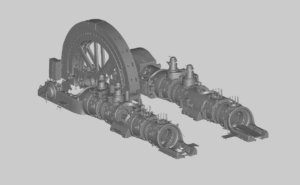

The final polygonal 3D model of the Groussgasmaschinn.

Processing an object as big as this was a challenge in itself. To make sure all the data was processed correctly, Artec 3D Tech Support Engineer Dmitry Potoskuev split up the process into several batches:

- He started with Ray data first. He cleaned up the data by removing all the unnecessary objects that the scanner picked while scanning the engine (using the Eraser tool), such as parts of the Gas Plant building, windows, walls, and various other equipment around the GGM11.

- Then he focused on unifying the flywheel and other parts data across all 18 scans by erasing specific data from some frames using the Eraser tool. This was necessary because several scans were done on different days, and the position of the flywheel and a few other parts changed a few times when the engine was turned on by GGM11 staff for demonstrations. This could result in some mismatches if those scans were merged as-is.

- After that, all Ray scans went through Global Registration to be registered between each other. Then each of the 18 scans were processed into meshes using the “Ray scan triangulation” algorithm with Polygon edge length (max) at 10 mm. This was done to filter all the surfaces with a large distance between the vertices, and as a result, to get a more detailed and cleaner surface afterward. After that, all the 18 triangulated meshes were processed using SharpFusion algorithm to create a single mesh aka “skeleton” of the engine’s model.

- The next step was to add all the details captured with Leo. Because of all the data (170 GB), Potoskuev broke the process down into several steps.

- First, he duplicated and locked the original Ray mesh. The duplicated copy was simplified to 5-10 million polygons and locked too. This was done to further the registration process. Next, he uploaded all Leo scans (divided into 17 groups during scanning) to the duplicated Ray project, and each of them was registered with the separately simplified Ray project for higher-quality alignment of data.

- After all the Leo scans were registered, Potoskuev selected the original Ray mesh and 4-5 raw registered Leo scans and applied the Sharp Fusion algorithm to create a new mesh. He repeated the process until all the Leo scans were processed with the original Ray mesh into a final mesh of the gas engine.

The final mesh consisted of around 350 million polygons, which were then reduced to 10 million polygons for further post-processing, using such features as Hole Filling tools, the Smooth Brush, and Bridges. The total processing time was all done within two weeks.

“With this gigantic engine 3D scanned, we can use this data to restore some missing parts and preserve it in its current state, so even if it loses its shape with time, we can still go back to this 3D model and show it to our future visitors, and use it for restoration purposes,” said Nicolas Didier, President and General Manager of the Luxembourg Science Center.

Artec 3D

www.artec3d.com

Filed Under: Uncategorized