In preparation for NASA’s Mars rover launch in 2020, researchers at Brown University published the geological history of a region on the red planet known as the Northeast Sytris Major—the most detailed of its kind. This region of the red planet is one of NASA’s final landing site choices. Since the primary objective of the 2020 mission is to find past signs of life, Sytris Major contains a lot of mineral diversity that includes deposits, which indicate past environments that could have supported life. The extent of those key mineral deposits across the Sytris Major’s surface were mapped out in high resolution images from Mars’ reconnaissance orbiter, which will also provide a comprehensive roadmap for NASA, should they choose this area.

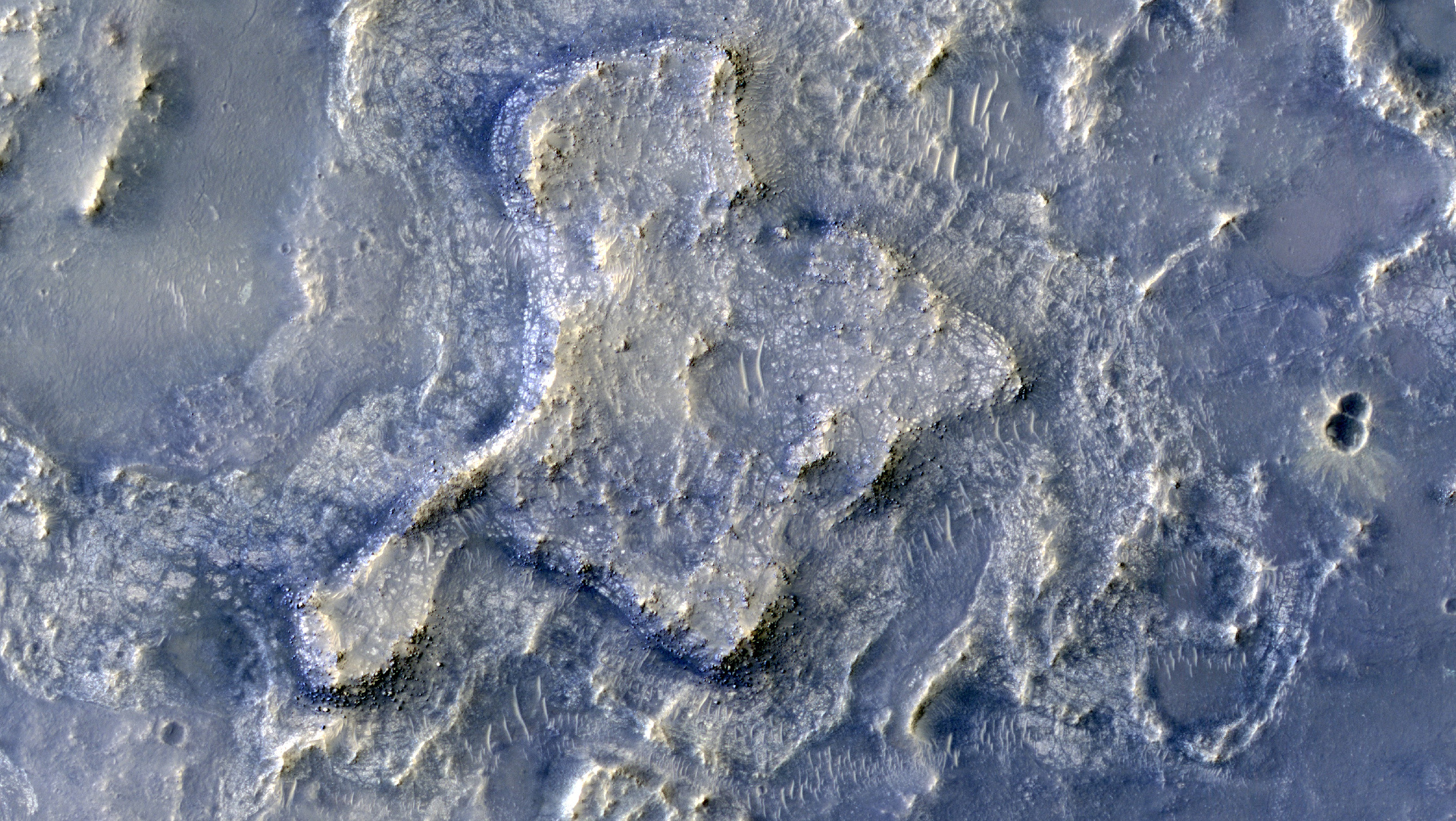

The region’s physical details, diversity of mineral deposits, and topographic layout were defined using false color imaging. Astronomers apply this process to enhance an image’s details from one another. Original satellite images were filled with whites, blacks, and different shades of gray. Since the human eye can distinguish up to 16 different shades of gray from each other, the extent of detail these images could reveal was significantly limited.

Each color shade represented the radio emission intensity from a particular section of an image. Astronomers converted these images to colored pictures, applying colors like red to an image’s most intense emission sections; blue to the least intense; and intermediate colors like orange, yellow, and green for other varying emission intensity levels. Black fills sections of images where no radio emissions were detected.

This even helped researchers distinguish the Northeast Sytris landing site over others, and even used the false color imaging process to identify up to four distinct types of mineral signatures that could potentially be found in what scientists perceive to be former aquatic and potentially habitable environments. Although the deposits in the Sytris Major were previously detected, the newly released map offers additional insights like how the minerals are distributed throughout the region.

False color imaging also helped researchers gain more insight on the geographical layout of the potential landing site’s region. The Northeast Syrtis is nestled between a crater that’s 1242 miles in diameter called the Isidis Basin and a volcano called Syrtis Major. Both landmasses formed between 3.7-4 billion years ago, with almost 250 million years in between each event. These formations occurred during the transition between the Noachian and Hesperian epochs—a time of significant environmental change on the red planet, which is why it’s so important for researchers to understand the timing of these environments.

False color imaging shows in great detail, the layout of the Northeast Syrtis Major terrain. (Image Credit: Brown University)

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense