Feature by feature, they revealed themselves: the plains of Sputnik, the Norgay Montes and the vast and forbidding Cthulu Regio.

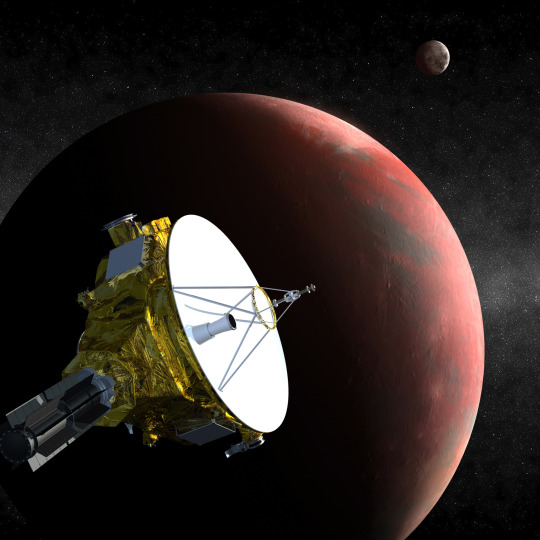

When the New Horizons spacecraft finally buzzed Pluto at roughly 30,000 mph on July 14, it sent back snaps of an untamed land of craterless plains and jagged ice mountains beyond our imagining.

Read more: NASA Mars Rover Moves Onward After ‘Marias Pass’ Studies

And those pictures of the dwarf planet traveled the expanse of space thanks to a 125-pound power plant that doesn’t know the meaning of quit.

It’s called the RTG, or Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator.

Originally designed by GE’s Space Division (now part of Lockheed Martin) in King of Prussia, Penn., this model of RTG has powered U.S. spacecraft since the Ulysses probe was launched in 1990.

The electricity from the RTG doesn’t propel the spacecraft, which use inertia from the launch and gravity slingshots around planets, but it’s necessary for the missions to snap pics, gather data and phone home.

The RTG takes advantage of the predictable decay of Plutonium 238, a radioisotope produced by certain nuclear power plants. The heat given off by the plutonium, which is in the form of 18 fire-resistant ceramic pellets, is transformed into electricity by a process known as the Seebeck effect.

Discovered by the 19th century German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck, the effect describes how heat can be turned into electricity when two different conductive materials in a closed circuit called a thermocouple are kept at different temperatures.

In a spacecraft, this means that the “hot” junction absorbs the heat from the plutonium while the “cold” junction is kept frigid by the near-absolute zero of space. The temperature difference between the two junctions results in an electrical current.

The internal heat source is necessary in space, where the sun’s energy is too weak to power solar panels. The RTG provided about 250 watts of power when New Horizons launched in 2006. But the device loses 5 percent of its power every four years and outputs about 200 watts currently.

GE was a critical part of the space race from its earliest days, working on computers, lunar landing modules, moonboots and even astronaut escape pods. But the RTGs were the most lasting contribution.

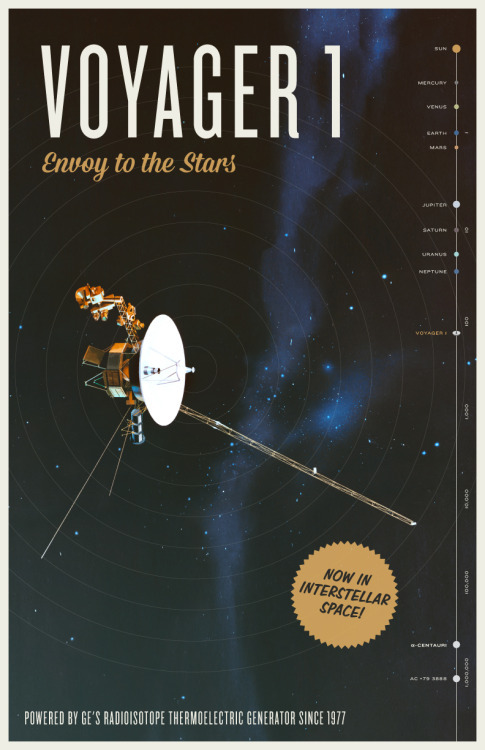

The older model RTGs GE engineered for the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft are still providing power for the craft, which have made it further from home than any manmade object in history.

The production of the thermocouples was stopped after the Voyager program in the 1970s sand GE had to kickstart it for the Galileo missions. The new model RTG, called a GPHS, or general-purpose heat source, used a different method to pack the plutonium fuel than the Voyager craft.

GE got out of the space business altogether in 1992. The company would still probably honor any service obligations, but the product is now a bit out of reach.

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense