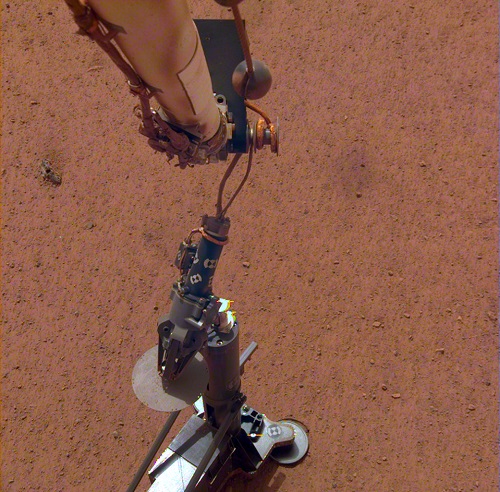

InSight is making great progress on Mars. Just this month, its seismometer was fitted with a protective dome shield. Now, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) reports InSight has placed its second instrument on the Martian surface, the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3).

(Image Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/DLR)

Situated 3 ft (1 m) from the seismometer, HP3 will measure the “heat moving through Mars’ subsurface and can help scientists figure out how much energy it takes to build a rocky world,” according to NASA JPL.

The instrument will burrow down as far as 16 ft below Mars’ surface, which is the furthest depth than any other Red Planet mission.

“We’re looking forward to breaking some records on Mars,” says HP3 Principal Investigator Tilman Spohn. “Within a few days, we’ll finally break ground using a part of our instrument we call the mole.”

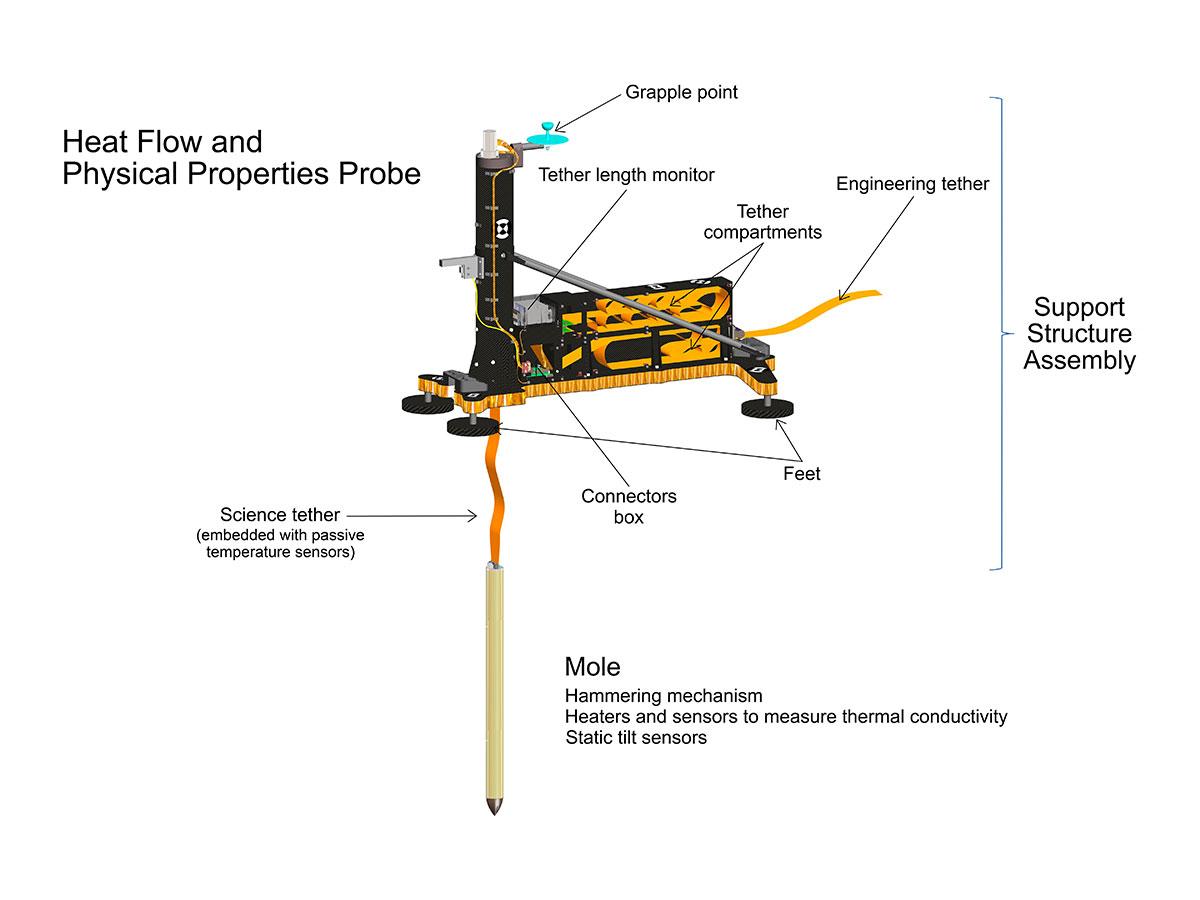

(Image Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/DLR)

HP3’s support structure is attached to the lander via a tether. Another tether, embedded with passive and temperature sensors, attaches to the top of the self-hammering spike (nicknamed mole). As seen in the diagram above, the mole is fitted with a hammering mechanism, heaters and sensors to measure thermal conductivity (how easily heat moves through the subsurface), and static tilt sensors.

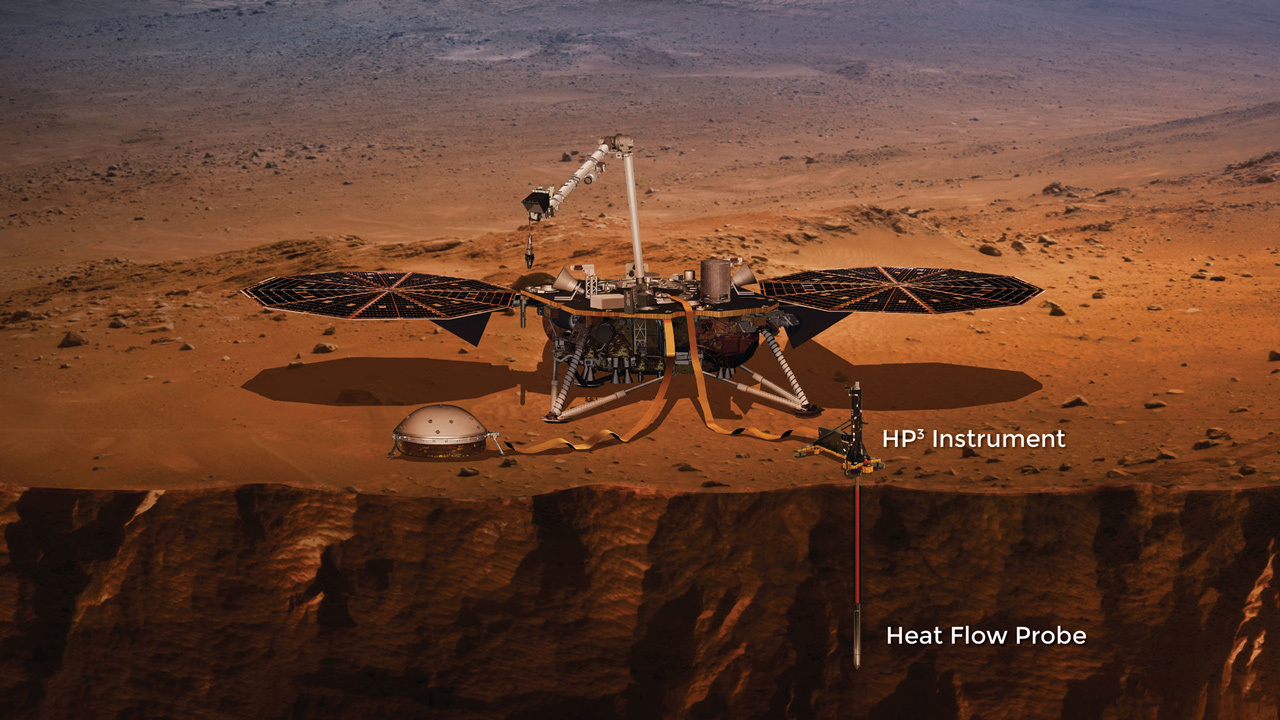

“Our probe is designed to measure heat coming from the inside of Mars,” says InSight Deputy Principal Investigator Sue Smrekar of JPL. “That’s why we want to get it below ground. Temperature changes on the surface, both from the seasons and the day-night cycle, could add ‘noise’ to our data.”

After every 20 in., the mole will stop its downward quest to warm up for the span of about four days. During this period, the sensors will determine how fast the temperature rise occurs, thus informing the team about the soil’s conductivity. Performing this regime, it’ll take the mole more than a month to reach 16 ft.

“If the mole extends as far as it can go, the team will need only a few months of data to figure out Mars’ internal temperature,” according to JPL.

However, one scenario in particular could delay progress. If, by chance, the mole runs into a sizeable rock before it hits 10 ft below the surface, the team will need to relegate a full Martian year (two Earth years) to sift noise out of the data. This is why the team picked a landing site that minimizes the probability of this situation.

“That thing weighs less than a pair of shoes, uses less power than a WiFi router and has to dig at least 10 ft [3 m] on another planet,” says JPL’s Troy Hudson, a scientist and engineer who helped design HP3. “It took so much work to get a version that could make tens of thousands of hammer strokes without tearing itself apart; some early versions failed before making it to 16 ft [5 m], but the version we sent to Mars has proven its robustness time and again.”

(Image Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Filed Under: Aerospace + defense