The first time Dan Arvizu thought about anything related to science or engineering was in the sixth grade. His teacher, John Price planted the seeds about a pathway that Arvizu hadn’t anticipated when he assigned the young student to write a paper on what matter was. Price was “one of the first people who gave me some level of encouragement along the idea of math and science,” said Arvizu.

The first time Dan Arvizu thought about anything related to science or engineering was in the sixth grade. His teacher, John Price planted the seeds about a pathway that Arvizu hadn’t anticipated when he assigned the young student to write a paper on what matter was. Price was “one of the first people who gave me some level of encouragement along the idea of math and science,” said Arvizu.

Arvizu was put on the middle-track math program in seventh grade until another teacher told him, “You’re moving more quickly than the rest of the class” and he was switched to the fast-track math program, maintaining it all the way through high school. By the time he was finishing high school in 1968, an aerospace career was on the mind of seemingly every kid.

“It hadn’t been that long since we’d gone to the moon, and so aerospace was kind of a big deal,” he said. “Frankly, I had never thought about college, even when I was in high school. I grew up as a son of immigrants. My dad finished third grade, my mom finished high school, and my dad finished his GED in the service.”

“I was influenced heavily by the fact that Alamogordo, N.M., where I grew up, is the town that supports Holloman Air Force Base. Holloman used the school system for the airmen and service people there, and as a consequence, they invested in education. A professor from NMSU would drive to Alamogordo to teach calculus in high school. I was in the faster track math grouping, so I was able to take calculus as a senior at Alamogordo High School.”

“Aerospace was what everybody wanted to do. Every one of my colleagues, my high school buddies, all said, ‘Let’s go be aerospace engineers.’ Four or five years later when I graduated, there were only two of us left that actually did it. After the first year, everybody else got weeded out by the calculus class, or the first-year math class.”

Arvizu started off as an engineer and stayed as an engineer. But over time, he said, the bottom fell out of aerospace engineering, and it was kind of a chaotic time in the U.S. with the energy crisis developing and long gas lines everywhere you went. He explained that those issues changed the trajectory of a lot of folks.

And they changed Arvizu’s trajectory, as well. Energy would turn out to a critical aspect to his professional life for decades to come.

Photo by Gary Mook

An energy-filled career path

Arvizu did the co-op plan through his undergraduate degree at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, a beautiful campus located near the base of the Organ Mountains. He worked at Texas Instruments in Dallas, which was one of several companies that made him offers at graduation time.

But his department head in mechanical engineering, who was a mentor to Arvizu, had told him about the opportunities at Sandia Labs in Albuquerque. Arvizu was intrigued, but Sandia wasn’t hiring. In fact, the lab was actively laying people off, as it was stuck in a political seesaw between funding for defense vs. energy (something that Arvizu notes pushed Sandia to strike a better balance between the two funding sources).

AT&T ran both Sandia Labs and Bell Labs, and a Sandia recruiter told Arvizu that Bell Labs was hiring. He soon discovered that Bell Labs did not hire engineers with a bachelor’s degree, but instead at the master’s level. Arvizu did some digging and found out about the lab’s One Year on Campus program, where they paid for graduate studies, hoping to have first dibs at the brightest master’s graduates before other institutions cherry picked them.

Arvizu was chosen for the program and was told he had to go to one of four top-notch institutions: MIT, Stanford, University of Illinois, or Purdue. Arvizu had never been outside of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. He was excited at the prospect, but he didn’t want to move too far away.

“I looked and I said, ‘Gosh, there’s only one that’s west of the Mississippi. I’m guess I’m going to Stanford,’” he said.

Arvizu received his master’s from Stanford. He went to work at Bell Labs and then switched to its sister lab, Sandia, to help start its energy program. He was part of the team that built Sandia’s power tower, a structure surrounded by a field of 222 mirrors (heliostats) that focused the sun’s energy on the central 220-foot tower. His job was overseeing the development of the heliostats.

“I was looking at everything from open-loop control to closed-loop control, and had to figure out how are we going to clean the mirrors? Each heliostat is made up of a 5×5 matrix of 5×5-foot glass facets. You had these mirror facets all situated in a configuration that allowed there to be curvature. They’re flat mirrors, but you put them in a curvature. The mirrors closest to the tower would have more curvature than the ones farther from the tower, and essentially could generate electricity that way. All of those heliostats focus up onto a focal point on the tower.”

“We would calibrate at night because the disc of the moon is about the same as the disc of the sun. From the focal point, you could literally see 25 moons in every heliostat. And then you’d orient the 222 heliostats — and you could actually get a moon burn!”

Rep. Torres Small Visits NMSU.

Around this point in his career, he realized that all of the people getting good promotions at the lab had PhDs, so he re-enrolled at Stanford and received his PhD. He was a bit of a pioneer in distance learning, as Stanford would send massive magnetic tapes of classes to Sandia for employees to watch.

Arvizu’s work also delved into the physical design of heat transfer of dimension PBX modules. PBX is a private branch exchange — when you dial the last four digits on a phone, that unit is the internal switching gear in a particular building, such as a hotel or office building. When someone dials the last four digits, it doesn’t go back to the trunk at the central station, instead performing local switching. Bell created PBX modules and Arvizu was a physical designer for them. But he was also interested at how to keep the cabinets cool — at a time before computers were as ubiquitous as they are now. Thus, he became one of the first people in the field working on the cooling of electronic equipment.

“Think of a refrigerator full of racks of circuit packs. Each circuit pack has electronic heat-dissipating components on it, and it heats up really fast. You put these integrated circuits in there and you plug them into the circuit packs — and you put those five levels of containers, and then you close the door. All of a sudden, you’ve got things that heat up very, very fast — and capacitors fail at 60°C. My job was to keep the electronics operating and cooled.”

“I was the first to develop forced convection cooling for electronic equipment. I would essentially put fans at the bottom of the racks … if you’re in a hot Arizona climate, somebody will put one of these things in a shed outside. I had thermostats at the top of the cabinet, and they would turn on these fans. It was the first use of forced conduction of electronic equipment in the country, even before laptops.”

Servant leadership

Arvizu eventually became part of a team that bid on running two different national labs before finally striking gold on the third try, the NREL in Colorado. When Arvizu became director in 2005, he was the first Hispanic to head a national DOE laboratory. He credits the culture at AT&T, which valued both professional development and diversity.

“For AT&T, it was in their DNA. They said, ‘We’re going to train leadership. We’re going to train managers so that they understand what they do,’ and it’s a kind of whole people training. So, it’s not just about how smart are you relative to your technical competency, but your people skills as well,” he said. “They were very good at embracing the idea that it’s important to have good communication and verbal skills in addition to being technically competent, because we all kind of know that if you just take your smartest engineer or scientist and make them a manager, they’re probably not going to do well.”

“There was a premium on diversity and on bringing skills other than your technical competency into the discussion when you started to move up the ranks in terms of leadership. What you learn over many, many years is: tone at the top matters. The tone at the top actually does infuse throughout the institution.”

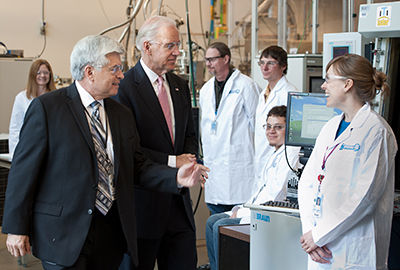

May 20, 2011 – NREL Director Dan Arvizu accompanied then-Vice President Joe Biden on a tour of NREL’s Process Development Integration Laboratory on Friday May 20. The PDIL has six bays where proven and experimental solar cells are made and tested in partnership with private industry.

Arvizu said that his first taste of in inclusiveness was when he was at Stanford. His thesis advisor had done an informal study on graduate students coming out of the university. They looked at the success of these students relative to their scores, both verbal and math on the ACT, SAT, and GREs — and determined that a better determinate of success was the verbal skills, not the math or technical ability.

“That obviously implies that there’s another dimension that’s important for success beyond your technical competence,” Arvizu said. “So that was clear to me at that time.”

Arvizu had the added benefit of a love for teams, going back to his childhood when he was in little league baseball.

“I enjoyed being on teams. I always excelled — my better self was brought out — whenever I was on a team, and I would rise to the level of the team. Sometimes the team will bring you down too! But if you have a good performing team, it really does improve everyone. As I mentioned earlier, the tone at top makes a difference. I was inspired by what I called servant leaders. There was a number of those that I had growing up, again, within the technical ranks at Sandia.”

“The thing about Bell Labs and Sandia was your first level of supervision is called a supervisor and then you go to department manager and then you go to director. Each one of those levels is very competitive. What you learn as you go through this process is that everybody’s smart. That’s never an issue. But then how well are you at bringing people together? How well are you at inspiring people? How well are you at getting the most out of each individual? That requires vision, it requires leadership, it requires care and feeding. It requires a variety of things that are more people skills, the soft skills. In addition to your competency, you’ve got to gain their respect first,” he said.

Arvizu said that as he moved into management roles, it became important to him to attract people that complimented his strengths and ultimately filled in his weaknesses.

“Understanding yourself is a really important thing. I’ve gotten more professional training than anyone can shake a stick at. I’ve done the social styles and Myers Briggs and a half a dozen of those. I’ve done them all more than once. So, I kind of have a pretty good feel for what my capabilities are and where my gaps are. We spent a lot of time at Sandia and AT&T looking at organizationally how do you fill in those gaps? When it comes to teamwork, when it comes to diversity, I’ve always been a big champion and advocate because I’ve experienced it, I’ve worked it, I’ve been blessed with having professional training beyond what today’s environment really allows in most companies. That has given me a great deal of grounding in what I think are the principles that are necessary.”

“If you’re trying to attract a diverse workforce, you need a diverse management team. You need to be able to walk the talk, practice what you’re saying. People don’t care so much what you say, they do watch what you do,” he said.

“I’ve had a very, very blessed experience in having great teams around me. Many times, people that are much better than me are doing a lot of great work — but there’s also importance in being the quarterback, being the orchestrator, being the person that sees the bigger picture, knows what people’s roles are, lets them do their job, and be their big cheerleader. I tell my team that your success is my success. Everything I can do to help you succeed is really what I’m going to do.”

Still contributing

Arvizu led NREL for a decade, long by the standards of a lab director, and helped to transform the institution into the world leader in renewable energy research and development, nearly doubling its research portfolio.

NMSU Chancellor Dan Arvizu tours the Pan American Center with Athletics Director Mario Moccia. (NMSU photo by Josh Bachman)

He’s been busy on other fronts, too, always giving back where he thinks it’s important. He was appointed by President Bush in 2004 to the National Science Board and confirmed by the full Senate for a six-year term. In 2010 President Obama reappointed him for another term, which ended in 2016. He was recently appointed by President Biden to the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). And while both postings were honors, Arvizu truly loves this new role.

“I’ve turned down at least a dozen different appointments that essentially were not kind of in line with my personal approach with my family and all that. But PCAST is particularly unique,” he said. “PCAST offers the possibility of not just doing something meaningful, but also to do it in a way that you can begin to implement and to start to really change the trajectory.”

“As you look at PCAST, it’s got five MacArthur Genius fellows. It’s got two Nobel prize winners. It’s got two former cabinet secretaries, and 20 members of the National Academies of Engineering, Science, and Medicine. So, it’s a very prestigious group, very well accomplished. I pinch myself every time I think about being on the committee.

Arvizu said that President Biden has tasked the committee with examining some important issues for the nation today. What did we learn from the pandemic? What kinds of things do we need to do different next time? How do we respond to climate change and best use science and technology for the coming energy transitions? How do we keep leadership of the U.S. scientifically, globally? And ultimately, how do we make sure that everybody participates in some meaningful way?

Back to his beginnings

In June 2018, Arvizu’s career took an unexpected turn, when he was asked to come back to New Mexico State University as Chancellor. Arvizu prides himself in being a bit of a turnaround specialist in other locations and in other endeavors. So, he jumped in.

“I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” he said. “Academia is harder than the public sector, the private sector, and the nonprofit sector. It’s been a rude awakening. As much as I like the idea of a meritocracy, the processes are highly political. You’ve got a legislature, you’ve got an executive branch, you’ve got elected officials, you’ve got donors, you’ve got mayors. Everybody is your boss. I used to say that at NREL, but I didn’t fully appreciate that it could even be more expanded in an academic institution.

08/10/2018: New Mexico State University Chancellor Dan Arvizu reacts while remembering his time as student living at Garcia Hall, about fifty years ago, during NMSU move-in day. (NMSU photo by Andres Leighton)

Arvizu explained that creating upward social mobility is an important part of NMSU, because the school is a minority serving institution. When he was a student there 50 years ago, the Hispanic population was less than 22%. Today it’s above 60%. And there are plenty of challenges for educational institutions today.

“Higher education has been declining in terms of enrollment, in terms of research, in terms of the things that you care about in your mission for a decade,” he said. “And problems started even before that. It is under-resourced in so many different ways. I’m thought, ‘Wow, the challenges are enormous. And my alma mater is suffering. What can I do to help turn that around?’”

Arvizu feels that the changing times means the university is not so much discipline focused.

He emphasized that it’s not so much about just being a mechanical engineer focused on one thing.

“It’s about being a mechanical engineer that is a problem solver that recognizes the value of teaming with the arts and sciences and the business community and the legal community — and putting all those together for solutions that actually benefit society,” he said. “That set of skills, that are collaborative, cooperation, communication, critical thinking, are part of the scientific method that we all learned, but they also now are the skill base for all of the industries of the future, no matter what discipline you’re in.”

Toward a renewable future

Given Arvizu’s long and storied career in energy, he has a lot of opinions about what’s coming next in the renewables industry. But what does he think the future of energy production looks like for the planet?

“There needs to be a transition,” he said. “We need to acknowledge the global aspect of this. It’s one thing to live in the U.S. or in Europe, where you have infrastructure, and you have investments, and you’re moving in a particular direction. And frankly, our greenhouse gas emissions are actually dropping over time because we’re going from coal to natural gas and making those transitions. When you go to the developing world, that’s where the major issue is with anything that relates to climate. We’re talking about Asia, we’re talking about India, and then Africa is right behind them, and then everyone else — they don’t have many choices. And they look at this global energy world very, very differently than we do in the developed nations.”

“You have to acknowledge that. As someone who has really spent their entire career in renewals, I remember when I was working on 1 cm x 1 cm solar cells, and people would look at me and say, ‘That stuff’s never going to amount to anything. What are you doing? We’re going to burn oil until there’s no more oil in the ground.’ Well, I don’t believe that. And in fact, 40 years of experience, to me, demonstrates that ingenuity, innovation, and creativity and an understanding with the right kinds of public policies, we can get to a better outcome. I’m convinced of that.”

Arvizu believes that if you can give people and countries more functionality at less cost, it’s a winner, plain and simple. Then you don’t have to worry about politics or whether you believe in climate change or not, because then it’s simply about economics.

“I’m persuaded and convinced that innovation and ingenuity, science and technology, does create the opportunity for us to advance in society, both in productivity (which we do every year in terms of GDP) and in the context of our infrastructures, whether it be health or energy. In this case in energy, the world is going to change its way in which we generate energy in the future. What I’m now persuaded and convinced by is that renewable energy will have a very, very, major part of our future.”

“And it’s because we now are able to harness solar. We harness wind, we harness geothermal, we harness a variety of other renewable technologies, biofuels, a variety of things that we can do — and they will make up the majority of what ultimately, is our generation mix. Whether it’s central station or whether it’s distributed is yet to be determined. I think in the developing world, you see more distributed. In the developed world, we’re already committed to central station, but they’re both compatible and I think there’s balance in both.”

“The bigger issue, to me, is what does the developed world do first? Because people will tell you, ‘Hey, if you do everything you want to do and get to net zero, and the developing world doesn’t change what they’re doing, it’s really for naught.’ Frankly, that’s where all the growth is, that’s where all the emissions are. If you listen to the people in the developed world, they say, ‘Look, don’t penalize us with your aspirations because you grew dirty in terms of the budget of carbon that you’ve already admitted. Don’t lecture us.’”

“How do you get past that dilemma? Well, you get past that dilemma by giving them a greater yes. You give them the opportunity to have more functionality at less cost. And so that’s why it’s important for us to keep pushing the envelope on the next generation, because ultimately, the developing world is going to adopt what is the best that we have to offer. Emerging economies didn’t go and build landlines 10 years ago. They went and did wireless, right?”

“Our challenge is to develop as many low cost, low carbon energy approaches as we possibly can. And then the rest of the world will follow because it is in their best financial interest. You have to be able to make it in their financial interest.”

You may also like:

Filed Under: Uncategorized